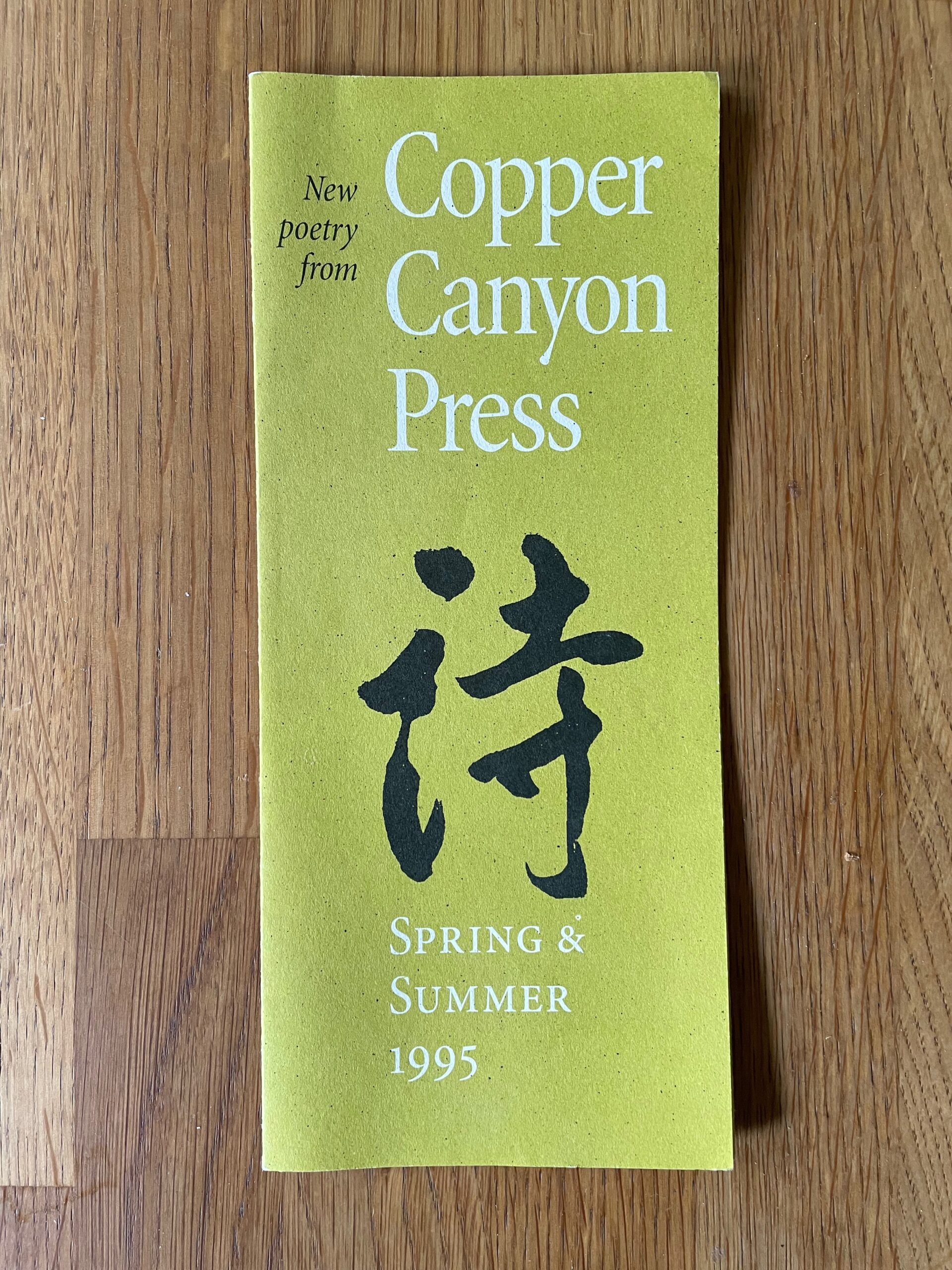

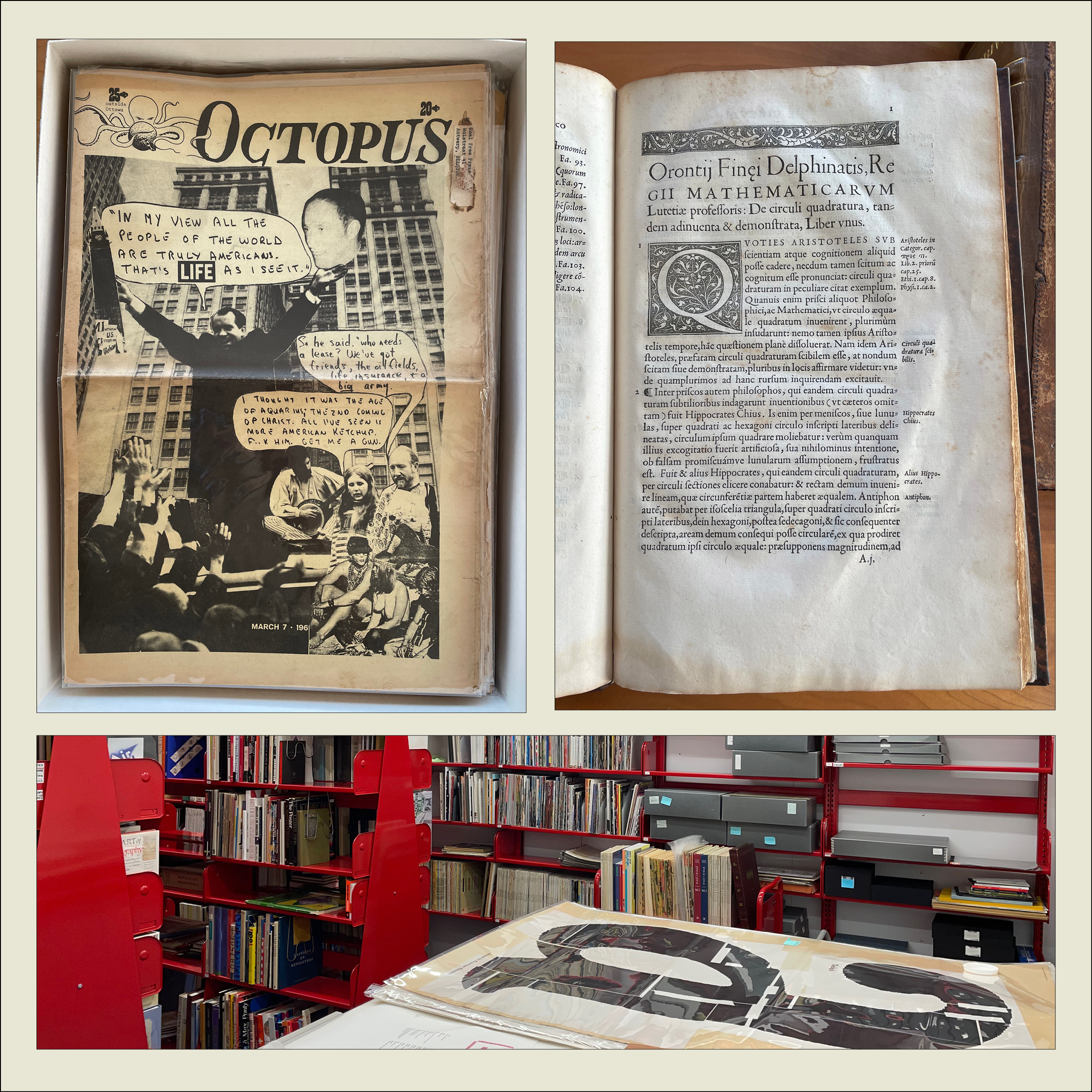

After a bit of a hiatus, I’ve come back to my sporadic typographic memoir, this time to talk about the years in the 1990s when I was the house designer for Copper Canyon Press. In that time, I designed not only the books but all the collateral material as well, trying to keep a consistent feel to everything that came out of the press while maintaining a variety of approaches to individual books.

This chapter is posted on Medium, as are all the previous chapters of the ongoing memoir project.

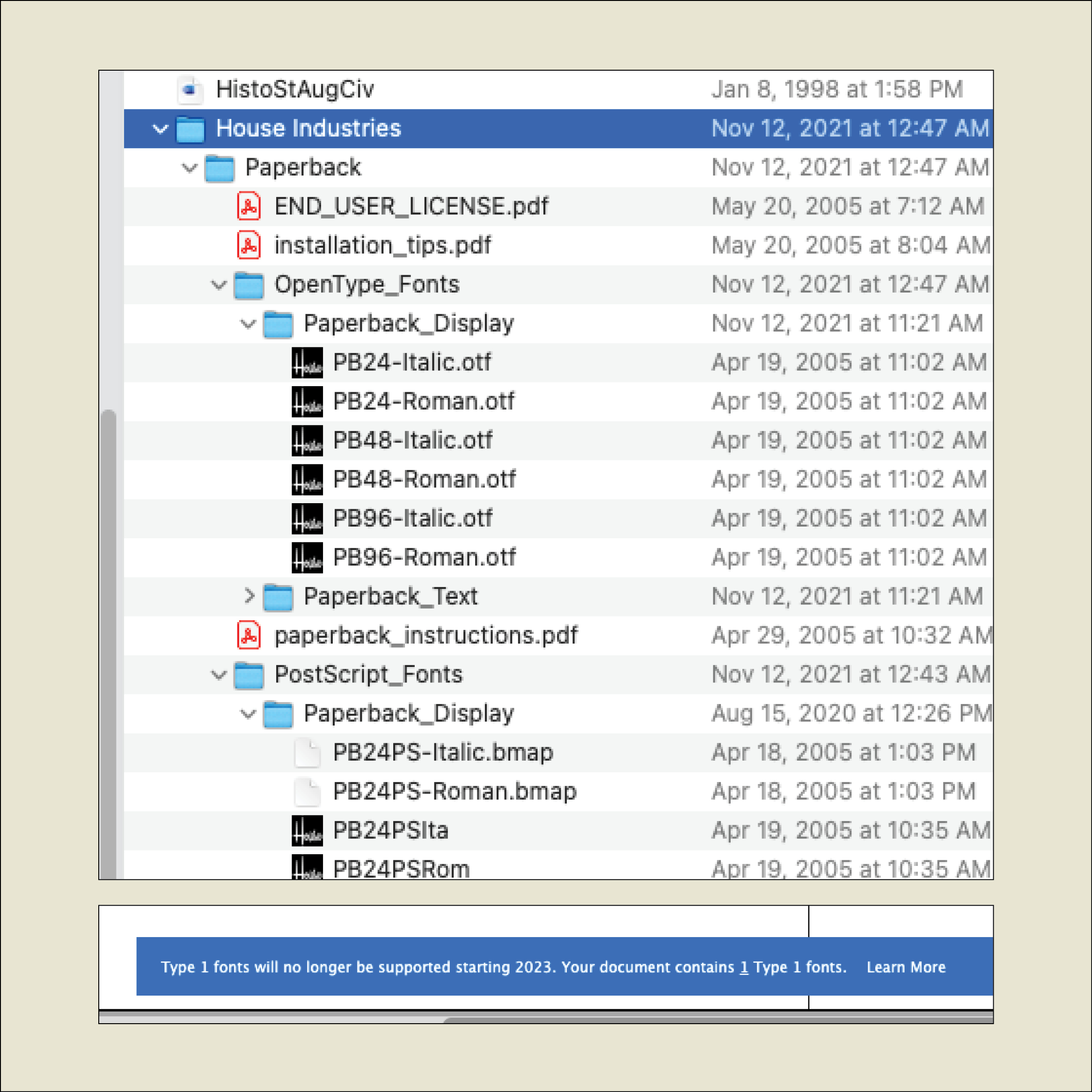

I still have all the files I created in producing those books, but I was working on a Mac before Apple adopted OS X, which fundamentally changed the file formats of the entire operating system. Unfortunately for future compatibility, all of those old files, none of which had filename extensions, now show up in the modern MacOS as “Unix executable files,” for lack of any other identification. Of course, the file information is still there; add the proper extension and the file type becomes recognizable. Whether it becomes openable, after something like a quarter century, is another question. But there are old Macs and old OSes and old versions of PageMaker. Somewhere.

In a few cases, I did create PDFs of my designs, either book covers or collateral like brochures. But any instances of Minion Multiple Master, the most advanced type technology of the time, which I used a lot, got lost in translation; current Adobe Acrobat technology doesn’t recognize the old MM fonts.

Such a waste of a brilliant technology! Such a short-sighted abandonment of sophisticated design. (Don’t get me started.)

Of course, with today’s variable fonts technology, you can get many of the same effects – and more. I just hope this tech doesn’t get left by the side of the information highway the way multiple-master formats did.

Really, isn’t the point to not lose information as techology advances? Including typographic and graphic-design technology. Our books need to be still readable in 500 years; or five years.