This is the text of the talk I gave yesterday at ATypI 2019 in Tokyo, about the project I’ve been working on for the past year: a history of ATypI. A draft of the first part of the history is now available on Medium.

*

I’ve given this talk the title “In Search of ATypI” because it really did require a search, to uncover the Association’s early history.

The Association Typographique Internationale (ATypI) was founded in 1957. The driving force behind the creation of ATypI was Charles Peignot, managing director of Deberny et Peignot, one of the most important French type foundries. (This, incidentally, is the reason why the Association’s name is in French.) The first official general meeting of ATypI took place in Lausanne, Switzerland, during an exhibition called “Graphic 57.” The list of people involved in that first meeting is a virtual Who’s Who of the type world of the 1950s.

Over the 62 years of ATypI’s existence, we haven’t always been very good at keeping records and preserving the association’s institutional memory. Most of the records we have are now kept at the University of Reading, but those records don’t go back past the 1970s and a little bit of the 1960s. And only some parts of them have been organized and catalogued.

When the Board of Directors commissioned me last year to write a history of ATypI, I had to see if I could find some documentation for those early years, and try to talk to the relatively few people left whose memory goes back that far.

My own involvement with ATypI began in 1990, when I attended Type90 in Oxford, my first type conference. So I have several decades of first-hand knowledge; but when ATypI was born I was barely seven years old. On the other hand, in subsequent years I served on the Board of Directors for fourteen years and as President for six, I have written quite a lot about typographic history, and I’m willing to talk to pretty much anyone while I’m doing research. So it may be that I was the right person to ask to write this history.

I only wish we had begun this project ten years ago. But I suppose everyone writing a history of a contemporary organization has a similar regret.

*

There are many boxes and file cabinets of ATypI records at the University of Reading, and right after the 2018 conference in Antwerp, I spent several days in Reading digging into those boxes. Some of them were well organized; some were not. My work was made easier because Ferdinand Ulrich had done some organizing and cataloging of the materials as part of his postgraduate research at Reading, so I had Ferdinand’s very useful outline of what kinds of materials we had and where they were in the archive.

And by following up on a couple of serendipitous leads, I discovered earlier collections of papers from both Charles Peignot and John Dreyfus, co-founders of ATypI and the association’s first and second presidents, respectively. These were not in Reading.

*

The Peignot lead came from Jean François Porchez, who was ATypI president from 2004 to 2007, and who organized the 1998 ATypI conference in Lyon. I stopped over in Paris for a couple of days on my way from Antwerp to Reading, and over dinner, Jean François told me that he thought that Peignot had given his papers to the Librairie Paul Jammes, a highly respected rare-book dealer. This antiquarian bookshop is located in a very old building in the heart of Paris, in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter of the 6th Arrondissement. The very next day, I visited the bookshop and met the director, Isabelle Jammes, the granddaugher of the founder. She was very helpful, but she told me that the Peignot archives had been donated many years ago to the Bibliothèque Forney, the city of Paris’s specialist library for, among other things, the graphic arts.

I had no time during my brief stopover to visit the Bibliothèque Forney myself, but luckily one of my American friends who lives in Paris is an art historian and editor, and she is also a member of the Forney. She was quite familiar with the library, she speaks French, and she was willing to go to the library and dig into the Peignot archive.

So I got permission from the Board to commission her to do exactly that.

It turned out that the Peignot archive, or “le fonds Peignot” in French, had an unusual condition attached to it: only items that had already been published could be photographed or scanned; original documents could not, although they could be quoted. This meant that Allison had to copy out by hand any information that seemed relevant.

Not all of the Peignot archive was concerned with ATypI, but among the papers were many records of early meetings when the Association was first being planned and when it first got going – the institutional memory that was missing from the archives in Reading. There wasn’t much personal correspondence, unfortunately.

*

But here is where the other unexpected lead comes in. One of the long-time ATypI members that I got in touch with was the Swiss book designer and publisher Erich Alb. Erich told me that John Dreyfus, the second president of ATypI, had donated four boxes of ATypI-related papers to the St Bride Printing Library in London many years ago, and recommended that I go find them.

When I got to Reading, I told Gerry Leonidas about this. I didn’t have time to go to St Bride’s myself, but Gerry of course is very familiar with the library and said he would visit it and see what he could find. A few weeks later, when he had a chance to do that, he discovered that the Dreyfus papers were indeed there, but that nobody had been aware of it. Apparently the four boxes had somehow been put into storage with their labels to the wall, so that they appeared to be just four more unidentified boxes in an already over-stuffed library.

What Gerry found in those boxes was exactly what we had been looking for: not just official documents but correspondence between John Dreyfus and other founding members of ATypI, including of course his friend Charles Peignot. There are missing pieces and blank holes in the historical record, but between the Dreyfus papers at St Bride and the Peignot papers at the Forney, we now have a fair amount of documentation describing how ATypI got started.

*

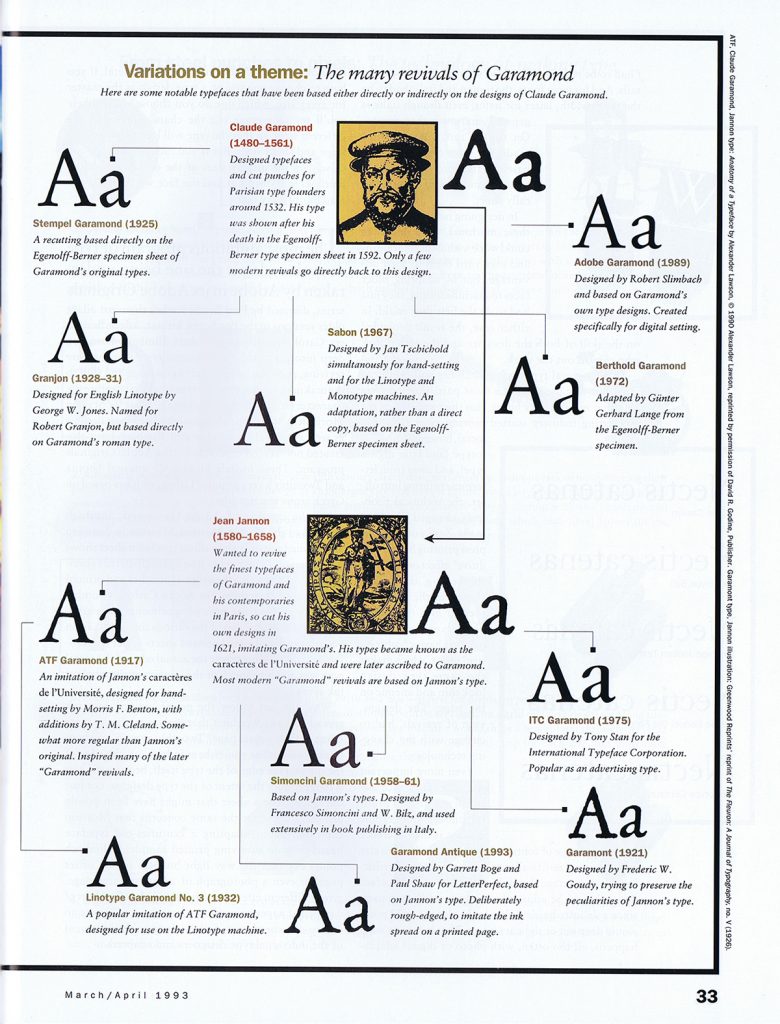

The impetus behind the creation of ATypI was the advent of phototypesetting, which Charles Peignot supported but which he thought would make it much easier for competitors to copy each other’s type designs. Of course, copying of designs goes back as far as the early 16th century, when the printers in Venice accused the printers in Lyon of copying their type designs. But it was a major feature of the type business in the first half of the 20th century, with each major foundry or type-machine manufacturer rushing out new type designs that would echo the latest popular designs of their competitors.

In those days, type was either set by hand or cast on a mechanical typesetting system. Those systems were not mutually compatible; each manufacturer made its own type that worked only on its own typesetting machines. Even if a foundry licensed one of its designs to a manufacturing company like Linotype or Monotype, the design would have to be redrawn and engineered to work on their system. (This was also true of the new phototypesetting machines.)

Peignot’s goal was to have type design included in the system of international standards that was governed by the Hague Agreement of 1925 on industrial designs. A large part of ATypI’s early effort was devoted to achieving this goal, including participating in endless international standards meetings and trying to establish ATypI as an expert voice on matters of type and typography.

As it turned out, all these efforts were for nought. The quest for international protection of type designs was a quixotic effort that, over the course of more than 60 years, has never fully achieved its goal. But that’s a story for a later part of the ATypI history project.

What ATypI did achieve, through the efforts of Charles Peignot, John Dreyfus, Jan van Krimpen, G.W. Ovink, and many others, was to bring the leading figures of the typographic community together, creating an international forum for discussion of type design and typography. When they started, they were thinking in terms of a “European Typographic Union,” which quickly expanded to become an “International Typographic Association,” including the United States and Canada. I wonder what the founders would have made of ATypI today, with our focus on education rather than industrial protection, and our expanded reach around the world. I like to think that they would approve.

*

So far, my research has been mostly about the earliest years of ATypI’s history, since those are the least known. But here are a few highlights from later years.

The 1967 ATypI Congress at UNESCO in Paris was the first to be a real conference, not just a series of business meetings. As Matthew Carter recalls: “Over time, people realized that this single question, the protection of typefaces, was not really going to be enough of a reason for ATypI to exist. So these annual conferences got more and more important in the life of ATypI. They became more social and less industry-oriented. That was a novel idea at the time, to have a program of talks and so on. As far as I remember, all of them since then have had a program, some degree of talks.”

In 1973, the early efforts at type-design protection culminated at the Vienna Congress, which was a general effort at revising international standards for the protection of industrial designs. A special agreement about type design was reached, and hopes were high; when John Dreyfus concluded his term as President later that year, he did so with a feeling of “mission accomplished.” But that turned out to be premature. The agreement required at least five countries to ratify it. In the end, only two countries did.

In addition to its conferences, ATypI sponsored a series of “working seminars” between 1974 and 1992, each one focusing on a particular aspect of type or typography. (As you know, a new series of Working Seminars has just been launched, beginning with the one in Colombo, Sri Lanka, earlier this year.) The 1983 Working Seminar at Stanford University, “The Computer and the Hand in Type Design,” turned out to be a seminal event, focusing attention on the new possibilities of digital typography. It was organized by Chuck Bigelow, who at the time was an Associate Professor of Typography at Stanford, and featured, among others, Hermann Zapf, John Dreyfus, Donald Knuth, and Jack Stauffacher.

Type90, the 1990 conference in Oxford, England, was ATypI’s first event to be open to the wider community of visual design. It was organized by Roger Black, and it was a typographic extravaganza, presenting both the traditions of type and the effects of new digital technology. Sometimes it turned into a clash of cultures: I remember the shock with which some people reacted to Zuzana Licko’s all-digital presentation with its rock-music soundtrack, in one of the hallowed halls of Oxford. From that date on, ATypI was more outwardly focused than it had been in its earlier days.

In 2009, ATypI held its first conference in Latin America, in Mexico City. In 2015, the first ATypI conference in South America was held in São Paulo. The first ATypI conference in Asia was held in Hong Kong in 2012, and now here we are in Tokyo for our second Asian conference.

*

We have just published a draft of the first part of my history of ATypI on the ATypI website, so you can go there and read it now. It’s just a draft; it will be part of the first book in the ATypI history series, which will be published in time for next year’s conference in Paris. I welcome comments and any new information from anyone who was involved in ATypI’s early years. I would be especially happy to hear from anyone who has usable images from those early years; what we have is pretty sparse.

Thank you for your attention. I hope this short talk has given you a bit of historical context for the ongoing project that is ATypI.

Categorized as culture, events, people, type designers, typography, writing & editing |