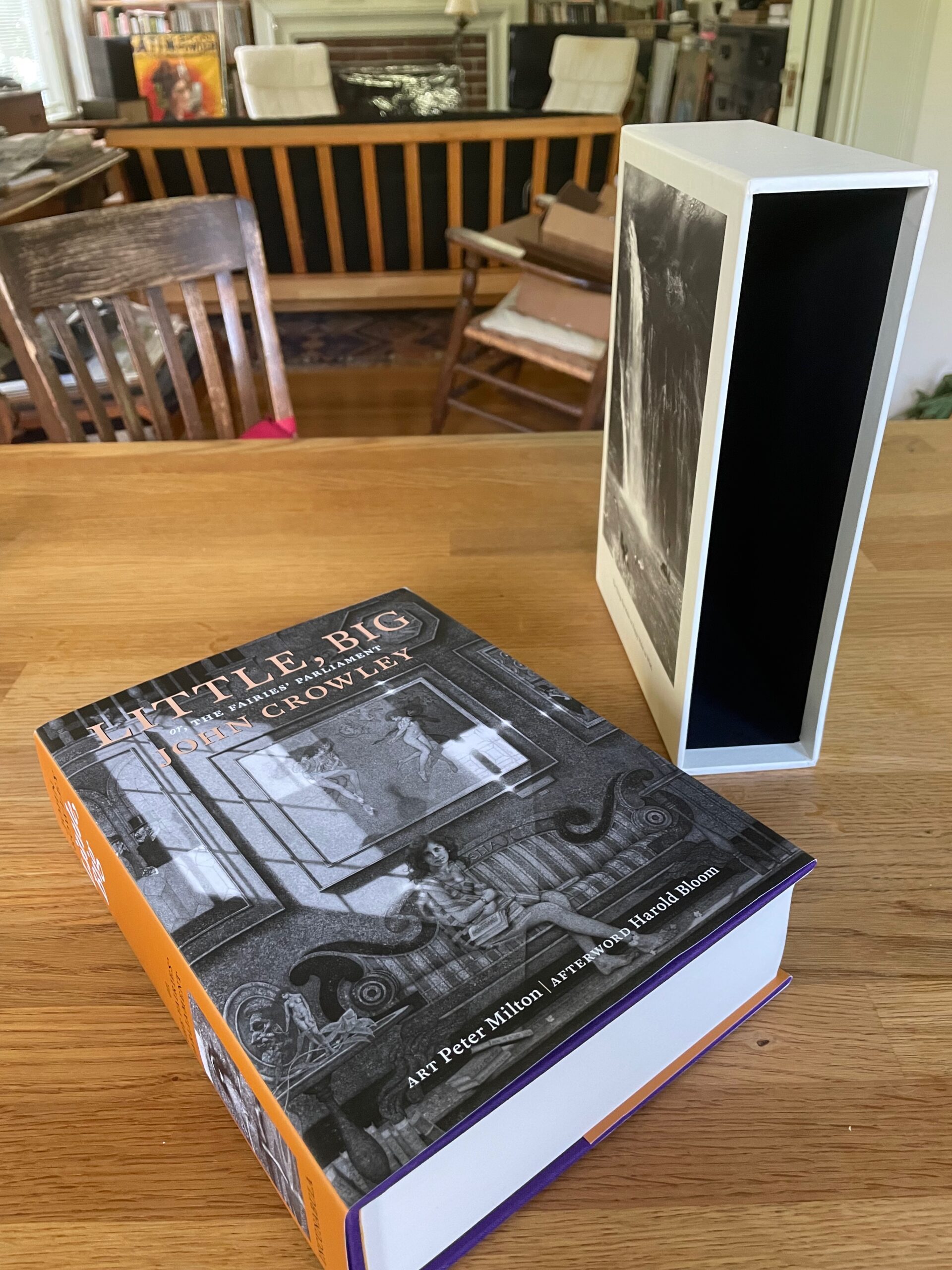

Last week, on a visit to Boston, I got to visit the Katherine Small Gallery in Somerville. It’s a gallery, because it does have exhibitions, but it’s most obviously a bookstore. An inviting, dangerous bookstore.

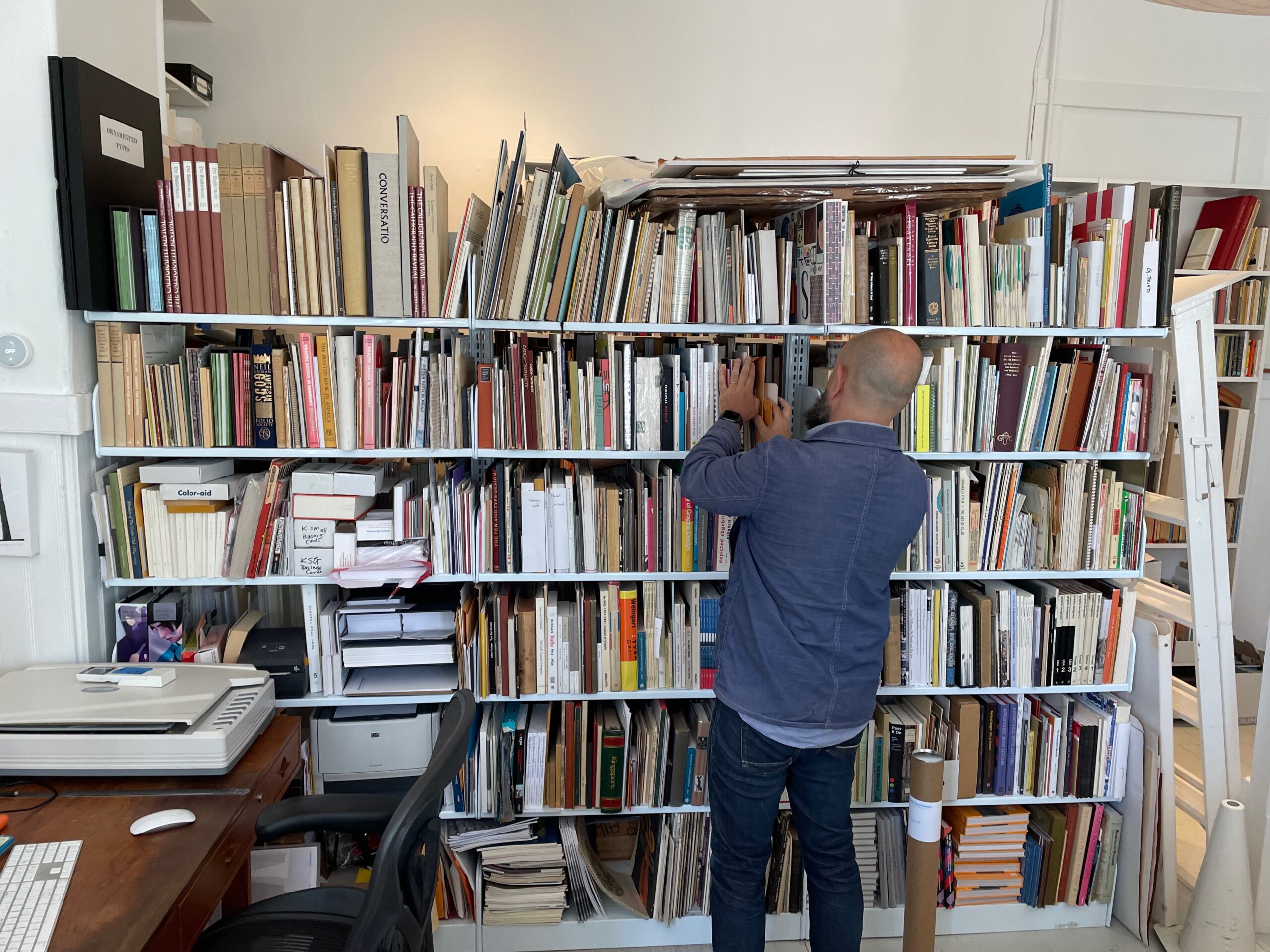

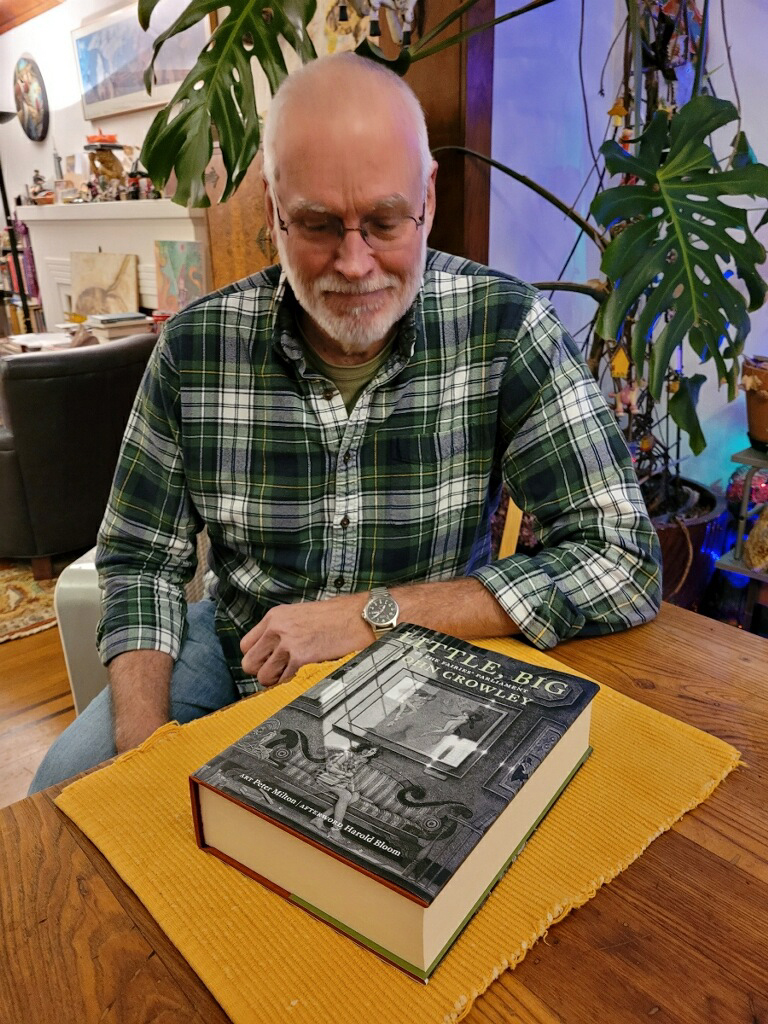

Michael Russem, the proprietor, greets each new arrival with the same welcoming line: “This shop deals only with graphic design and typography, so lower your expections!” If your tastes and interests are anything like mine, however, this introduction will only raise your expectations. And the shop exceeds them.

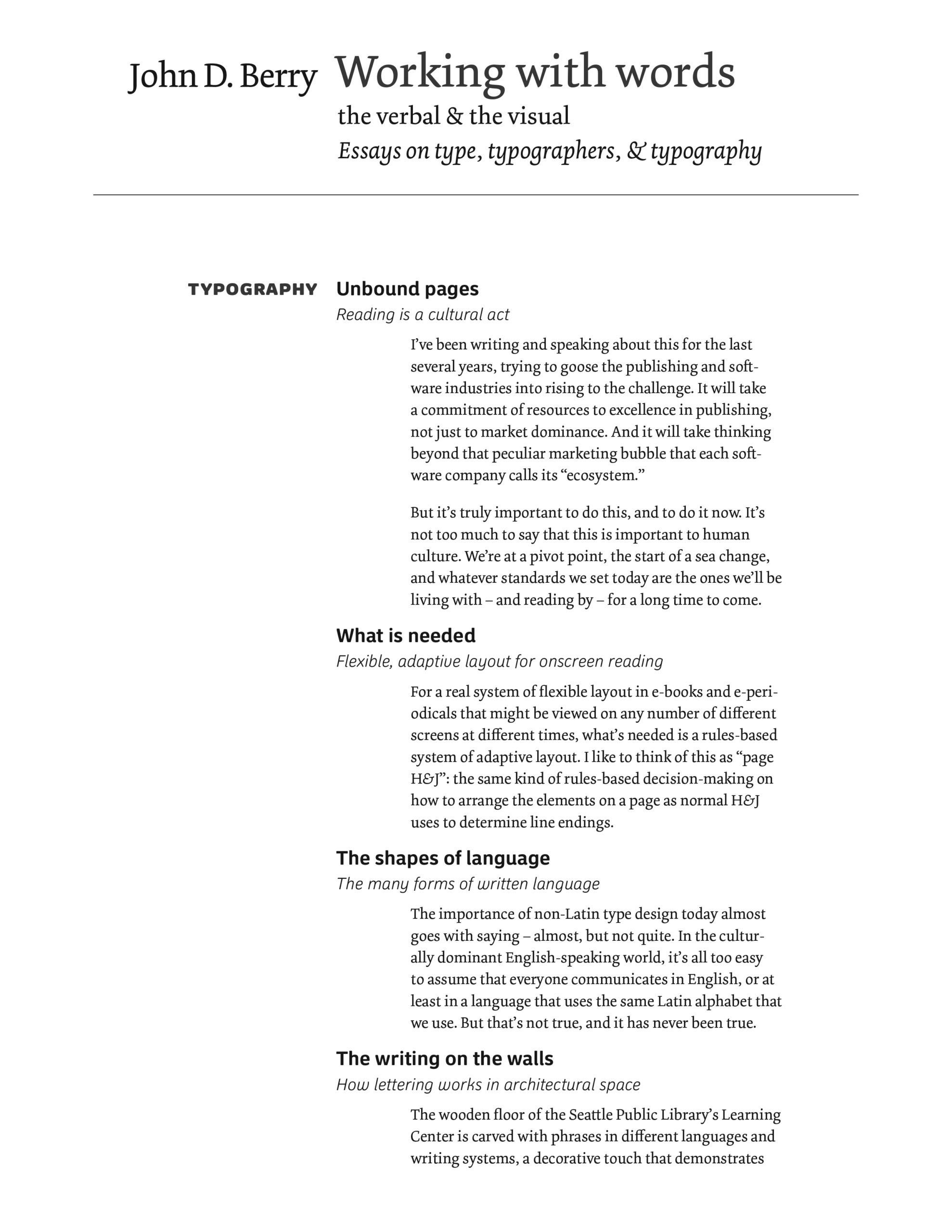

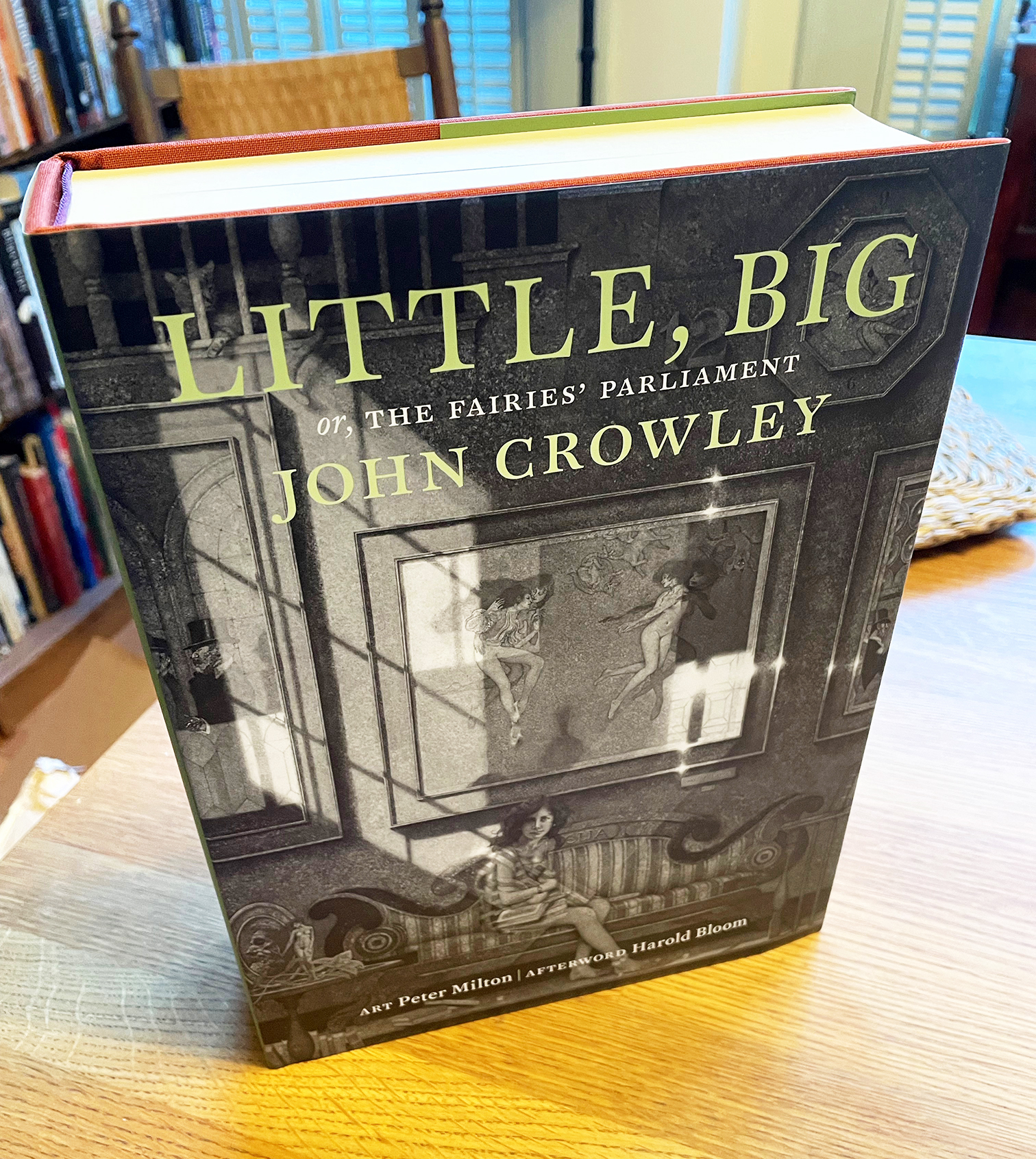

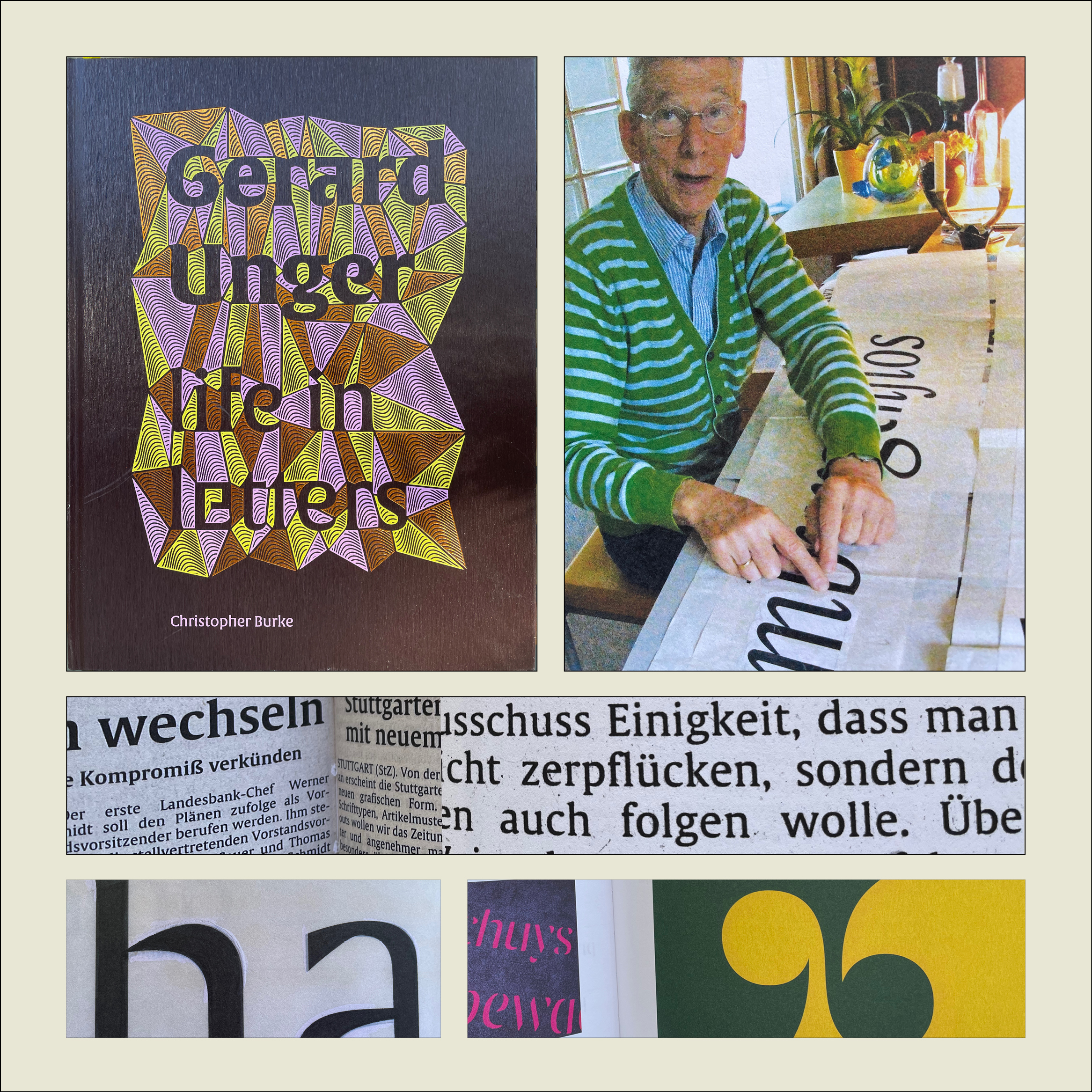

The shelves are full of books about typography, both current and rare. I was relieved to see that many of the most inviting were books that I already possessed; but not all. Naturally I ended up leaving with a bag full of books, which Michael bundled up in such a way that I managed to fit them into my carry-on bag for the flight home. (Such restraint I showed! As I told him, if I had wandered into a shop like this thirty years ago, I would have bought far more of the books – if I could have afforded them.) Then there was his own collection, which were not for sale but were displayed behind the desk and available to browse.

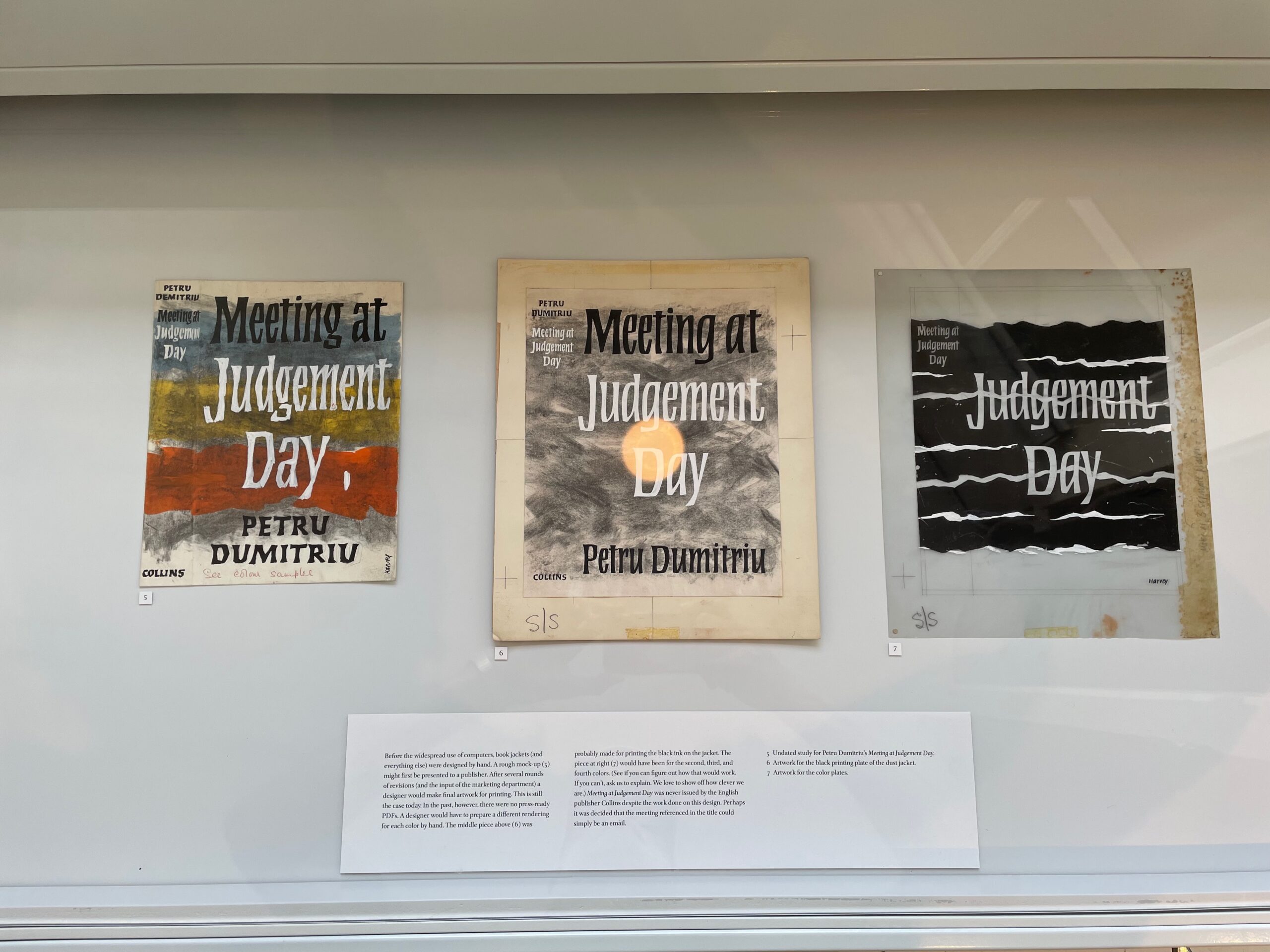

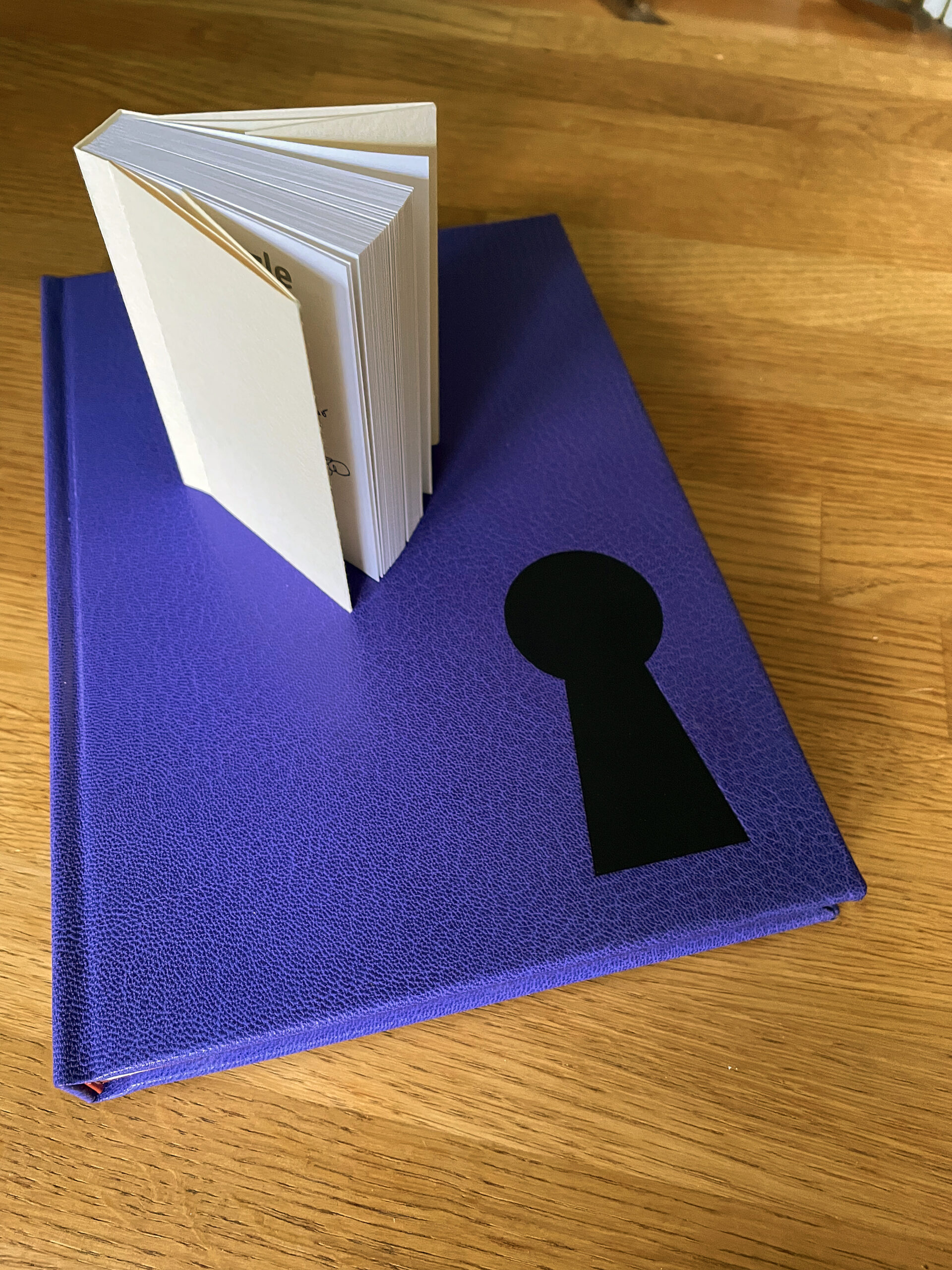

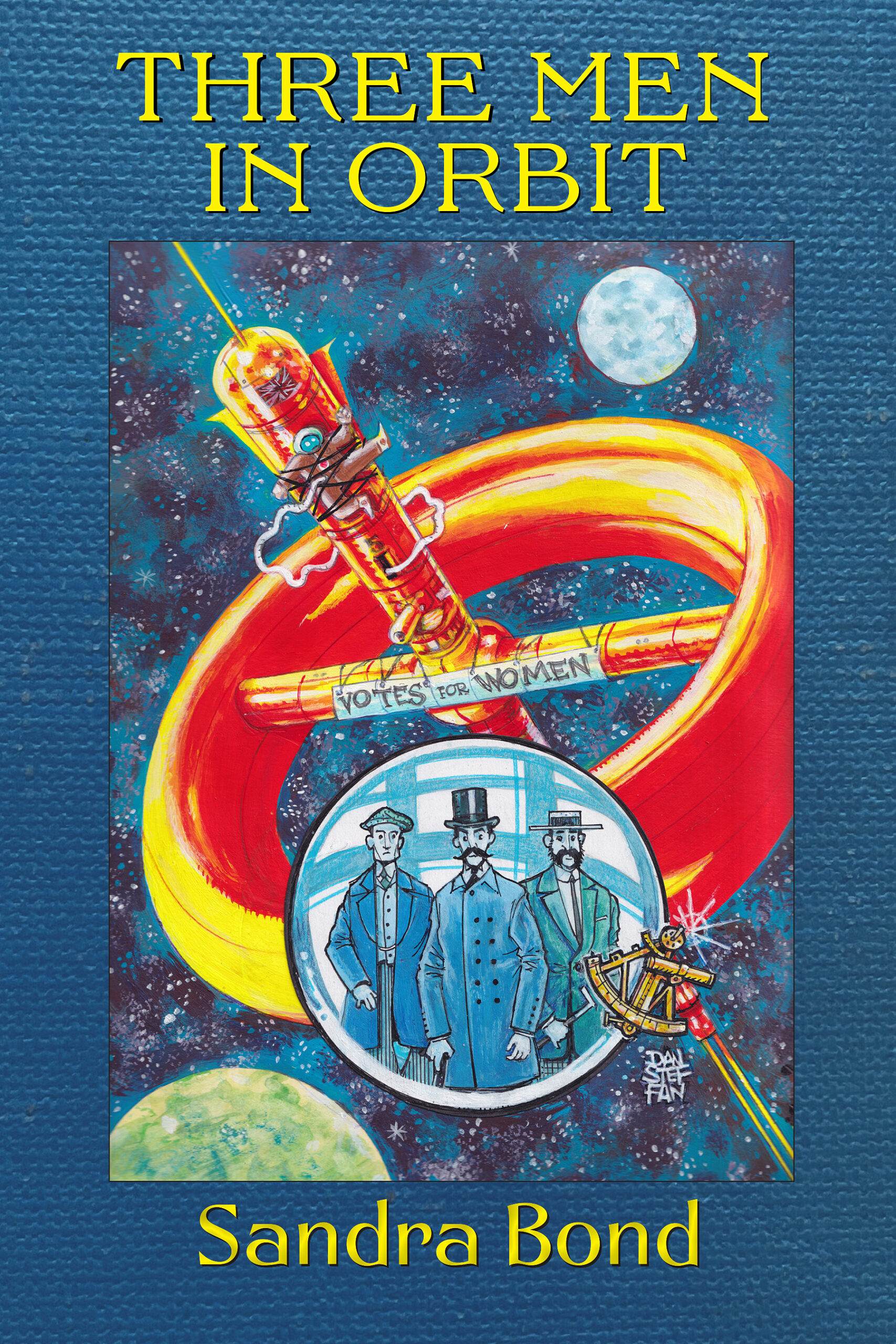

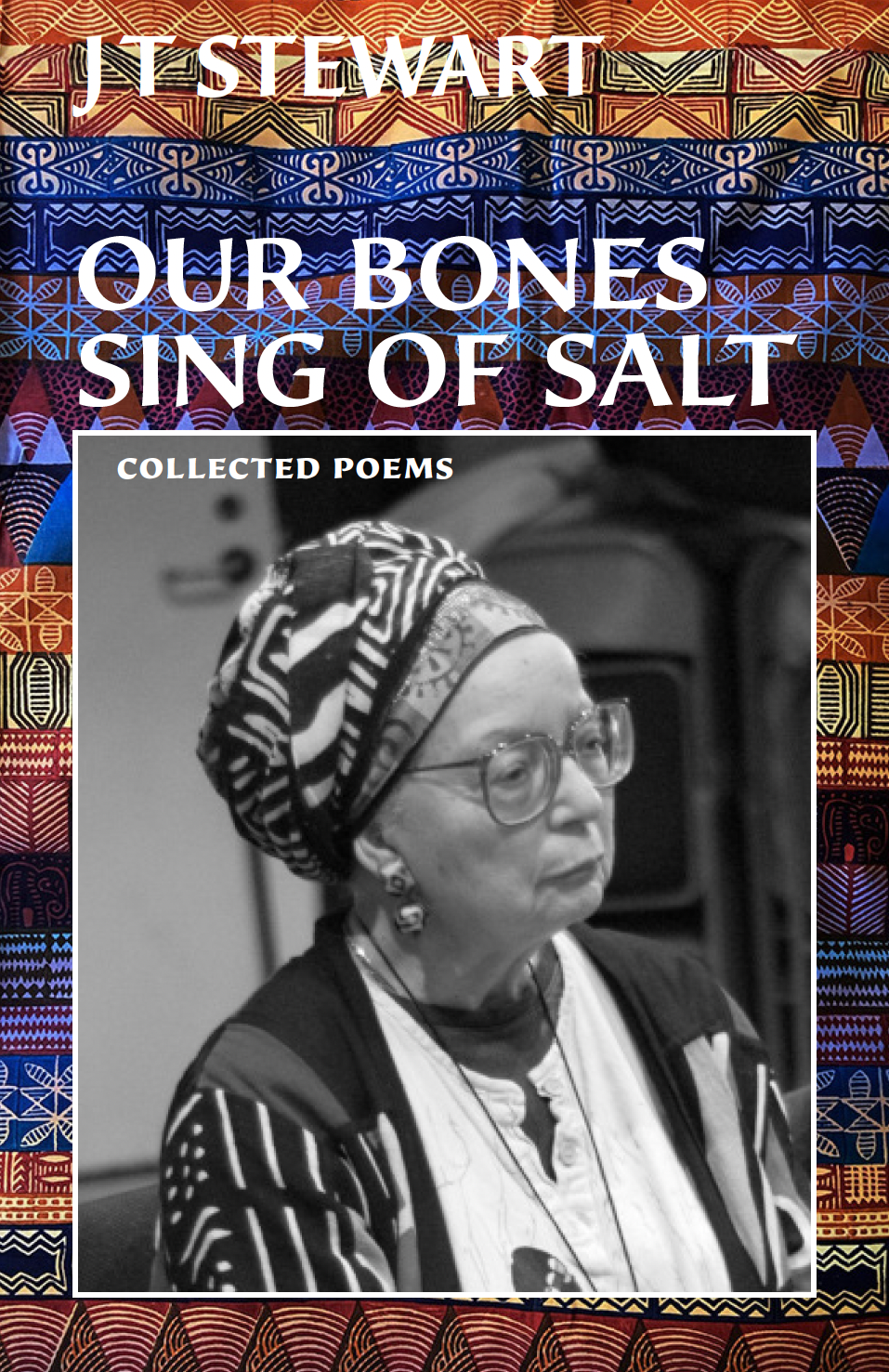

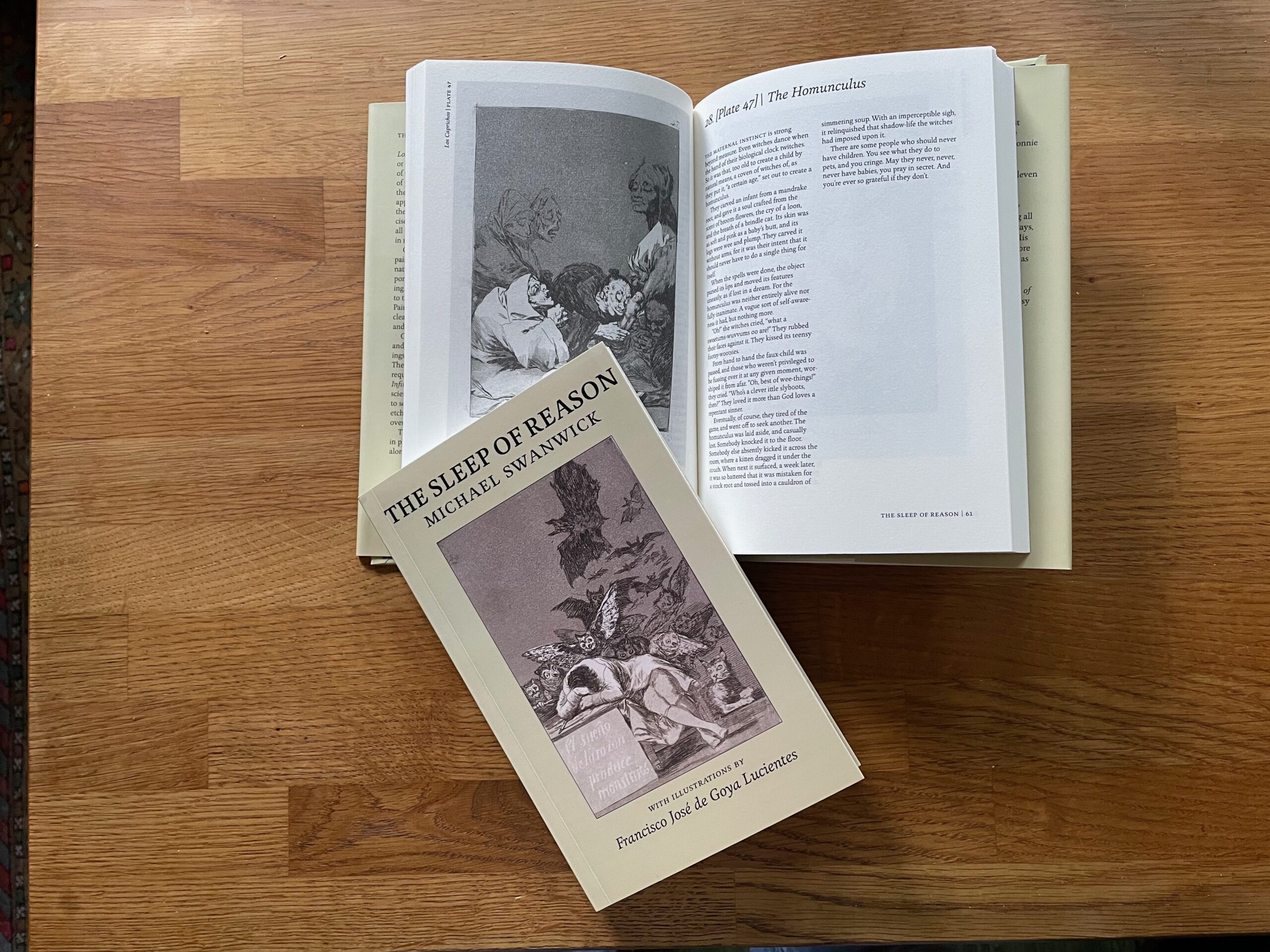

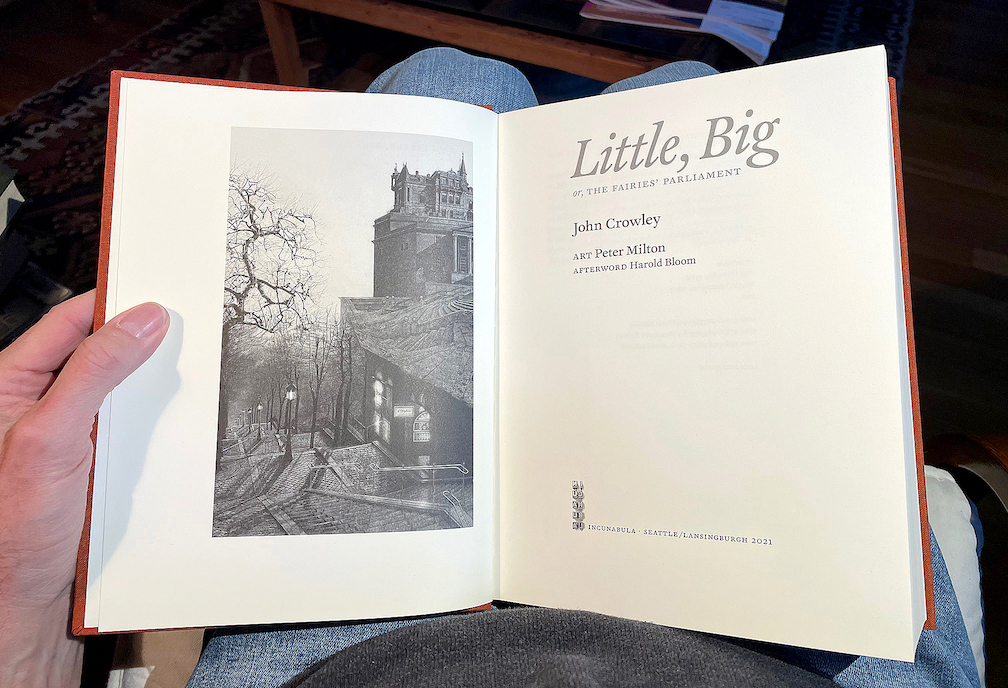

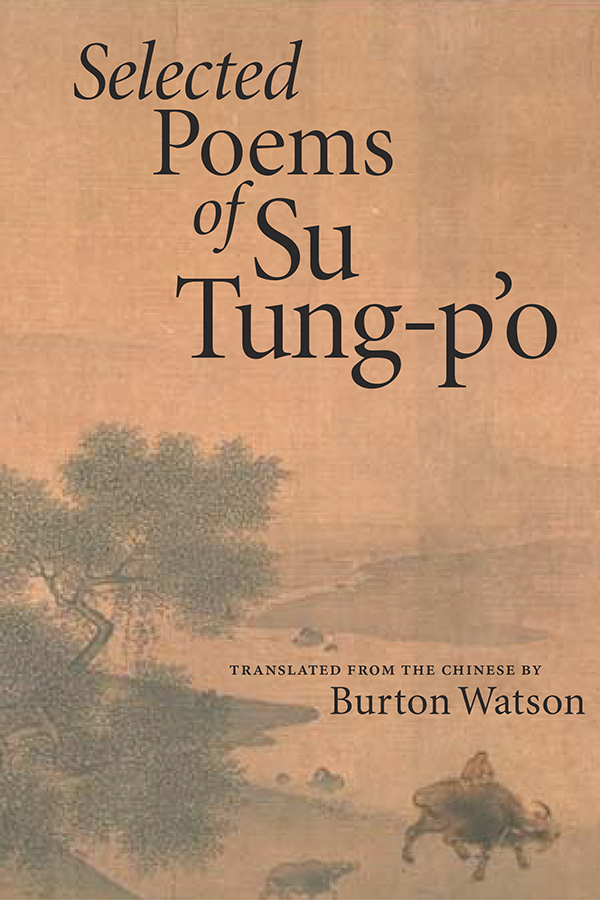

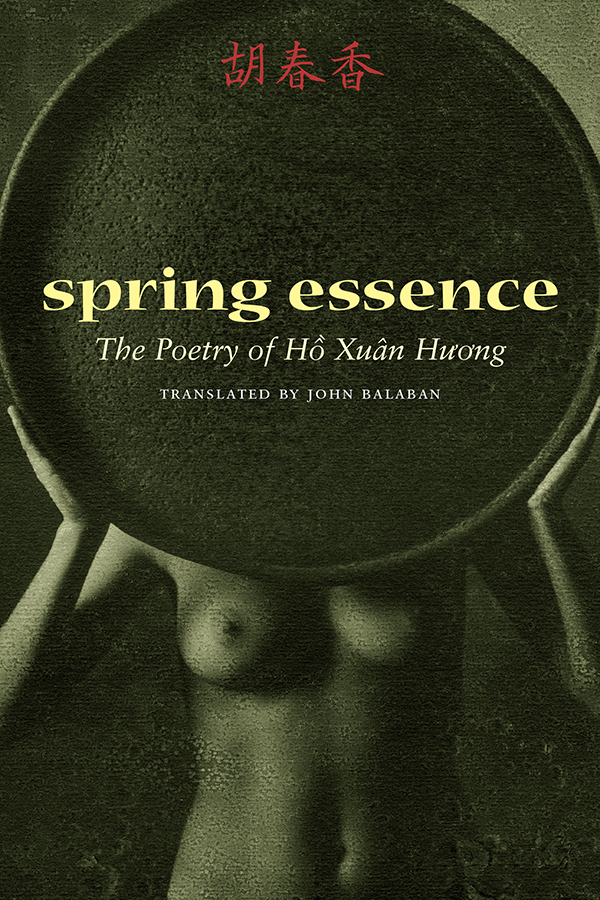

In a fit of perfect serendipity, I found that the current exhibit was on the book-jacket designs of Michael Harvey. I am a big fan of Michael’s distinctive lettering style (and of the man himself, now much missed), so this was a must-see for me. The germ of the exhibit was a small collection of mock-ups for covers and jackets, which were exhibited alongside the finished dust jackets. The glassed-in tops of two display cases were full of Michael Harvey designs, and flat-file drawers underneath them held many more.

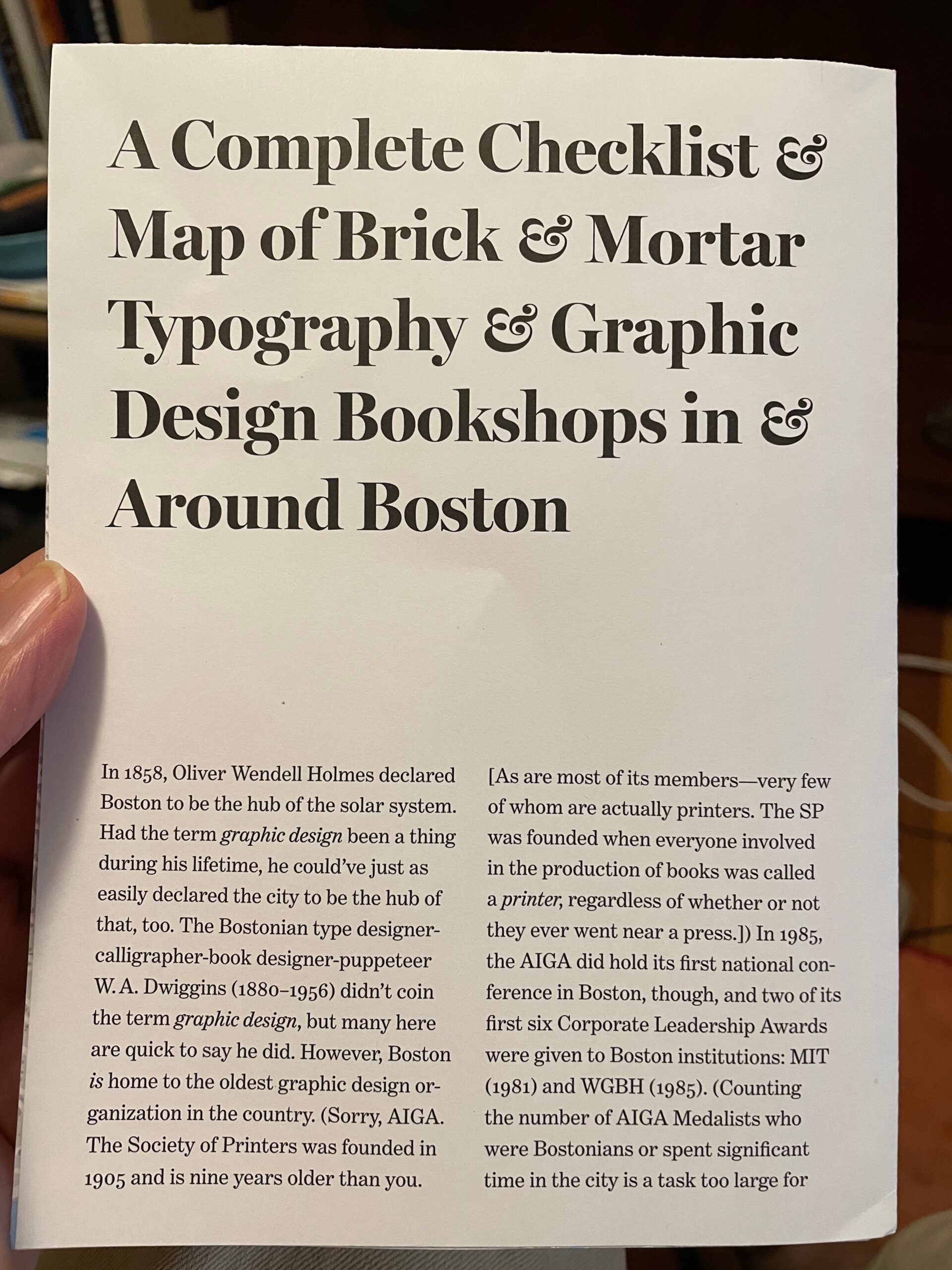

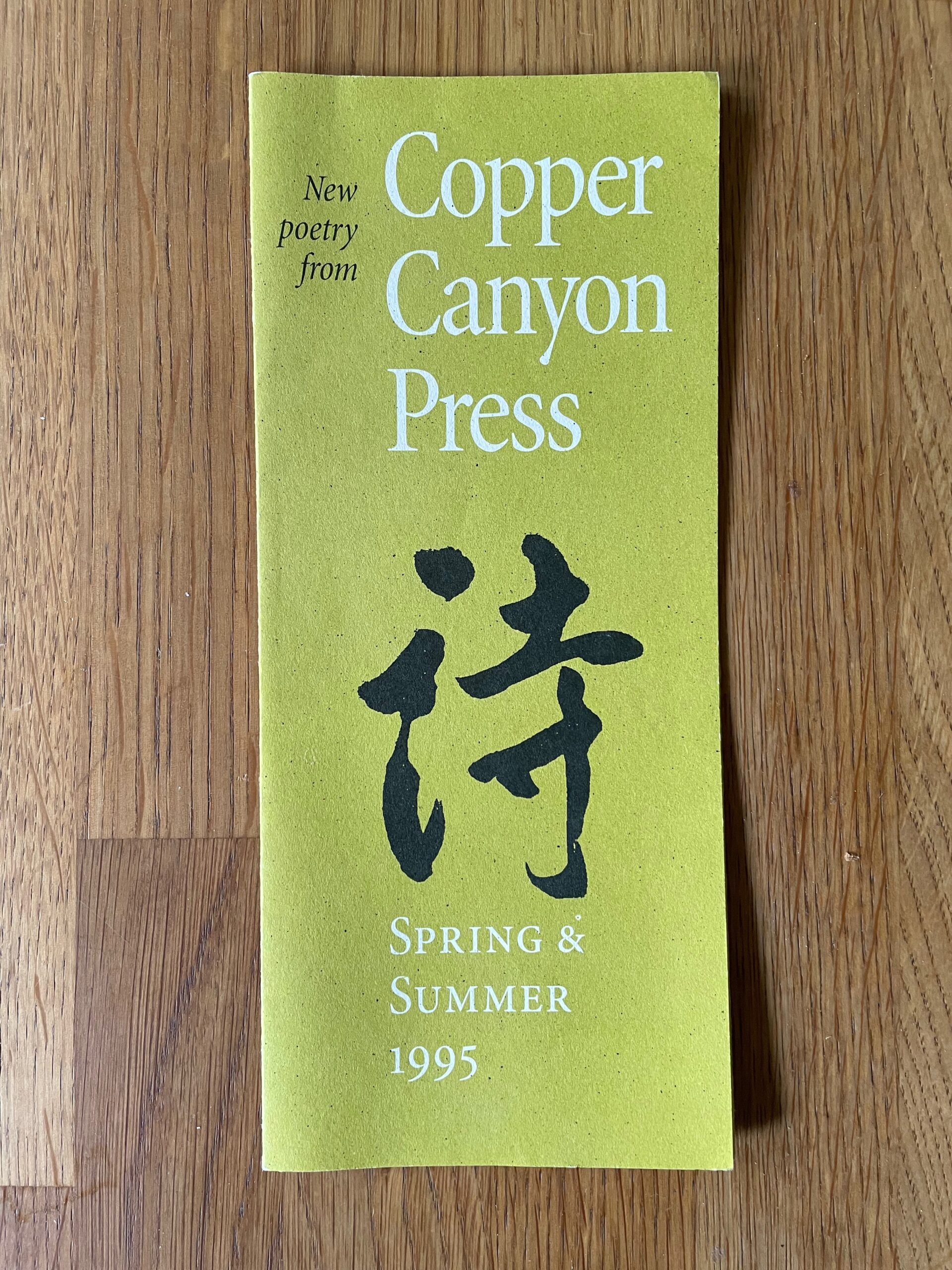

I can certainly recommend a visit to Katherine Small Gallery if you’re in the Boston area. Michael Russem’s dry sense of humor is displayed in the folded map that he handed me: “A Complete Checklist & Map of Brick & Mortar Typography & Graphic Design Bookshops in & Around Boston.” Open it up and you find a lovely map of Boston, with exactly one shop: his.

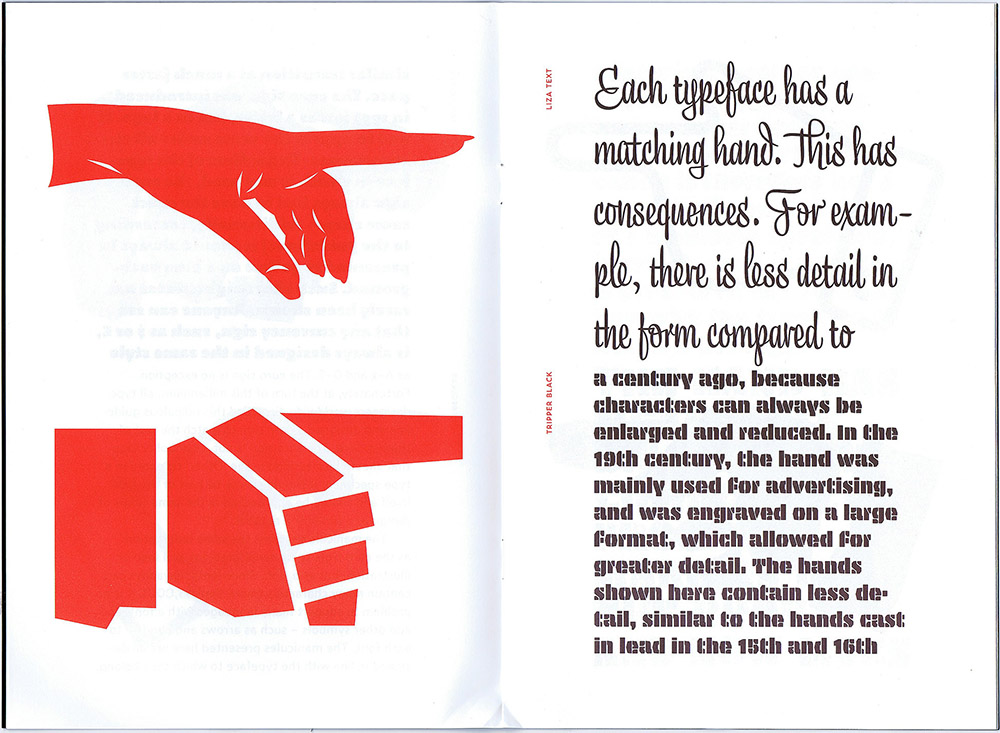

[Top: Proprietor Michael Russem at the bookshelves behind the desk. Middle: a display case showing three sketches/mock-ups by Michael Harvey for a book jacket. Bottom: “A Complete Checklist & Map of Brick & Mortar Typography & Graphic Design Bookshops in & Around Boston.”]