I’ve been intending to write an article about Steve Renick and his work ever since his sudden death in 2002. Even before that, I had the idea in the back of my head. And clearly, such an article needs to be written, since when I google him in various ways, in search of the best link for his name above, in the first sentence, everything I come up with is partial and oblique. But this is not that article; it’s just a few notes towards one.

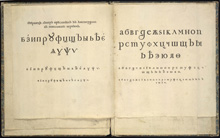

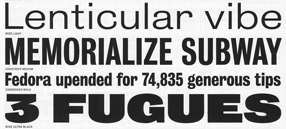

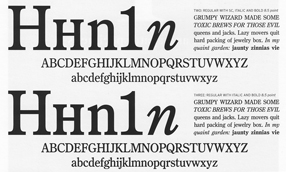

There isn’t a current exhibit of Steve Renick’s work that I can point you to, unless you drop by the offices of the University of California Press, where he was Art Director for twenty years. In their library/meeting room, last time I was there, they had a lot of Steve’s work on display; even without that intention, any display of books from UC Press in the past two decades would show a lot of Steve Renick’s work, either as designer or as art director. He was a consummate book designer, with an understated style in a sort of classical Modernist tradition. He was a typographer in the best sense; I remember that he had a Monotype type-specimen poster, from the days of hot-metal typesetting, under the glass top of his drawing table. We would talk about typefaces and books and the details of typography; I believe it was he who gave me a photocopy of the long-out-of-print book by Geoffrey Dowding, Finer Points in the spacing & arrangement of type.

I would try to visit Steve at the Press whenever I was in the Bay Area. He was always friendly, helpful, informal, and curious about whatever was new. I remember arriving one day when he had just gotten his hands on a Mac and an early version of QuarkXPress; he was noodling around, trying things out, finding out how the software worked, thinking about how he could incorporate these new capabilities into the way he designed books. At that point I had never used XPress, but I had been designing and typesetting books digitally for several years; we compared notes on digital type and how it was set.

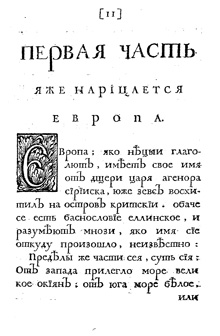

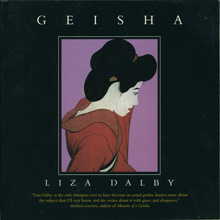

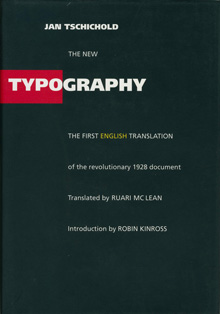

Many of the most high-profile books to come out of UC Press were Steve’s work, either designed by him or produced under his art direction: Henry Thoreau: a life of the mind, with Barry Moser illustrations; Geisha, by Liza Dalby; Poles apart: parallel visions of the Arctic and Antarctic, by Galen Rowell; the Allen Mandelbaum translation of Dante’s Inferno. He designed the remarkable English-language facsimile edition of Jan Tschichold’s Die Neue Typographie, the first time this classic of Modernist typography had appeared in English. That book, in fact, I had some responsibility for: I had been corresponding with Ruari McLean, Tschichold’s biographer and sometime translator, about getting his unpublished translation of Die Neue Typographie into print, when I found out that UC Press, all unknowing, was contemplating commissioning a translation, not realizing that a translation already existed in manuscript. I got hold of Steve, who put me in touch with the editor of the project; then I got the editor and McLean together and then left them to work out the best way to approach the book.

In contrast to his elegant, spare book designs, Steve’s hobby was fixing up old hotrod cars. (No doubt the engine details were as finely crafted as his typography.) I recall the first time he drove me to lunch in his current rod, and how flabbergasted I was at the apparent aesthetic contradiction of these two wildly different styles.

Steve was famously generous with his time and advice; everyone who has worked with him, been on a book-show jury with him, or just spent time with him remembers this. He was also resolutely unpretentious; in a group photo from a book-industry event, he would be the one over on the end with the rumpled jacket and oblique tie. He had an eagle eye for typography and a fine hand for design; his influence is easy to spot in the work of innumerable younger designers. Most of all, for book buyers and readers, he quite simply produced a wealth of books that we can read easily and that we can feel happy to have on our shelves.

Categorized as book design, publishing, typography |