More history, this time my own. As I worked on researching the first part of a history of ATypI, I came to realize that I myself had been around long enough that my recollections formed part of typographic history. So I’ve started writing down my memories of how I got involved with typography – a sort of typographic memoir. I came to type sideways, like everything else in my so-called career. I’ve just posted a draft of the first bit on Medium. Return with us now to those thrilling days of yesteryear…

easilyamused |

Archive for the category ‘writing & editing’

Franklin Press

Published

Garamondiale

Published

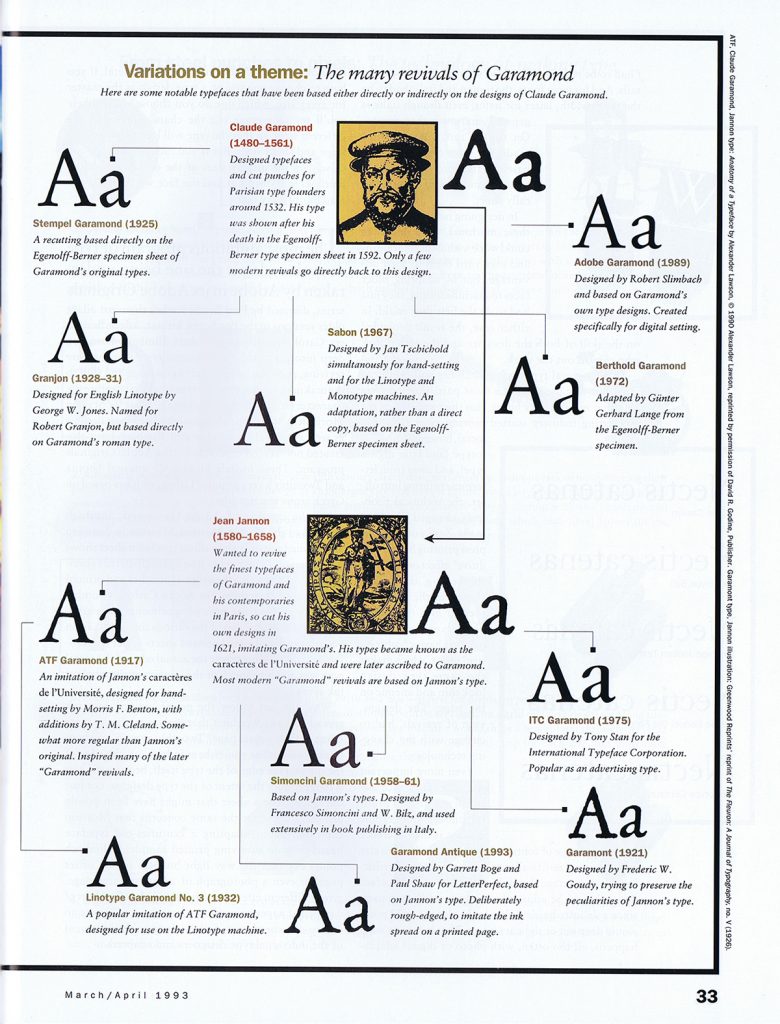

There always seems to be another Garamond. Eight years ago I wrote about this proliferation, not for the first time, inspired by an article that James Felici had just written for Creativepro (“Will the Real Garamond Please Stand Up?”); in that blog post I reprinted a thumbnail version of the “Garamond family tree” that I had first put together twenty years earlier for an article for Aldus magazine about typeface revivals.

By 2012 there were many more Garamond versions than my attempt at a family tree had dealt with, notably Robert Slimbach’s masterful Garamond Premier Pro. And of course there are still more versions today, including a libre version available from Google Fonts, called EB Garamond, that is based on the 1592 Egenolff-Berner type specimen, and Mark van Bronkhorst’s faithful recent revival of the popular ATF Garamond. (Full disclosure: I wrote the promotional copy for digital ATF Garamond.)

I’m not quite prepared yet to attempt an update of that Garamond family tree, but it might be a project worth pursuing. The tree would certainly have many more branches now than it did almost thirty years ago. But the primary distinction remains: between type designs based on Claude Garamond’s original 16th-century punches, and those based on Jean Jannon’s more baroque 17th-century imitation, which for a long time were attributed to Garamond.

Another distinction appears in the various italics. Although Claude Garamond did cut italic types, many of the Garamond revivals eschew his design in favor of an italic based on his contemporary Robert Granjon’s italic types, which type critics often find more finished or more elegant. The italics cut by Jean Jannon have yet another style, even more baroque than his romans.

(“Baroque” may be the wrong word, given some of the very different types from the 17th century that have been described as baroque by type historians, but it seems to me to capture the slightly more ornate style of Jeannon’s types compared to Garamond’s.)

The most commonly used version today is undoubtedly Monotype Garamond, which is the “Garamond” font family installed with every Windows system, and which therefore is what most people think of when they see the name “Garamond.” Monotype Garamond is based on Jean Jannon’s 1615 types, and in its more interesting alternative (not the version shipped with Windows) its italic features ascending letters with varying angles, instead of the regularized slope more common in type revivals.

For practical use right now in digital typesetting, the most useful Garamonds are probably Garamond Premier Pro and ATF Garamond – one based on the original Garamond types, the other on the later Jannon iteration. Both include extensive OpenType features, and both come in multiple optical sizes, for optimal use at different sizes in text or display. Both families also include a Medium weight, slightly heavier than the Regular, for an alternative, more robust effect in running text.

In Wikipedia, I currently find myself referenced three times in the footnotes of the “Garamond” article – though not, interestingly enough, for my 2012 blog post or the Garamond family tree in Aldus magazine.

John D. Berry, ed. (2002). Language Culture Type: International Type Design in the Age of Unicode. ATypI. pp. 80–3. ISBN 978-1-932026-01-6. [The reference is to Gerry Leonidas’s article about the history of Greek type design, including the Greek types cut by Claude Garamond.]

Berry, John D. (10 March 2003). “The Next Sabon”. Creative Pro. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

Berry, John. “The Human Side of Sans Serif”. CreativePro. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

Type designers have never been able to resist playing with the letterforms of Garamond and Jannon. There are two sanserif versions that I know of, ITC Claude Sans (originally published by Letraset, designed by Alan Meeks) and František Štorm’s Jannon Sans (which is a more extensive six-weight family, to complement Štorm’s even more extensive Jannon type family). Yet another branch for the ever-growing family tree.

Hanging by a serif (again)

Published

The visual concept behind Hanging by a serif came from something I was playing with for our 2012–2013 holiday card. “The stockings were hung by the serifs with care…” read the front of the card; inside, the text continued, “…in hopes that typographers soon would be there.” On the front, a wild cacophony of huge serifs barged in from the outer edges, with little green Christmas-tree ornaments appended to a couple of them. The background was a pale-green image of a potted conifer, drawn in stained-glass-style, taken from an image-based “Design Font” that Phill Grimshaw had designed in the 1990s for ITC. (The inside also featured a pale background image from the same font, this time of a wrapped package.) It was fun, though I wondered what our non-typographer friends and family would make of it when we sent it out.

Later that year, I began experimenting with the concept, juxtaposing short snippets of text from my own writing with big details from various serifs. I found that I had a lot of statements or fragments on the subject of design that seemed to fit into this format. Eventually, these epigrams and serifs took the form of the first edition of the book Hanging by a serif.

That first edition caught the eye of Bertram Schmidt-Friderichs, whose Mainz-based company, Hermann Schmidt Verlag, has published so many excellent books on typography and design. Bertram wanted to do a German edition of my little booklet, which would be a nice calling card for his publishing program and might even sell a lot of copies. (It didn’t.)

Bertram’s approach to publishing is thorough, and he wanted to include notes about which typefaces all the serifs had come from. This sent me back down the rabbit hole into my own production process, since I had been working with truncated images for most of the design of the book, and I hadn’t kept very careful track of what typefaces my serifs had originally been attached to. It took quite a bit of retrospective detective work to find all my sources. (Hint: a couple of the images had been reversed.) In this sense, the German edition is more thorough than mine. It also has a couple of serifs or serif-like glyphs that are different from the ones I used.

But one of the epigrams bothered Bertram: “Most graphic designers never get more than rudimentary training in typography.” While true, this struck him as too negative, and he suggested coming up with a replacement. In the end, we went with a statement in German that translated as, “Typography is never an end in itself, it targets the eye of the beholder.” (Probably pithier in German.)

When it came time to do a new English edition of the book (since I was running out of copies of the original), I decided to make two changes. The serif I had used on the cover of the first edition was taken from Justin Howes’s ITC Founder’s Caslon, a digital reproduction of William Caslon’s original types in which Justin attempted to re-create the exact effect of the metal type printed on hand-made 18th-century paper. The outline, therefore, was rough. This roughness around the edges bothered a number of people, some of whom asked me if perhaps the image had been printed at too low a resolution. It hadn’t; this was precisely the effect that the typeface was designed to have, but blown up to extra-large size like this, it was distracting. So for the new edition I searched out a new serif that would work well on the cover. (The serif I chose is from Matthew Carter’s newly released type family for Morisawa, Role.)

And I did replace the problematic epigram that had bothered Bertram Schmidt-Friderichs, though not with the one we used in the German edition. As I had mentioned once in this blog, a quip of mine had been making the rounds of social media for some time, being quoted repeatedly out of context, and I thought it really belonged in this compendium. So if you turn to page 16 of the new edition, you’ll find this: “Only when the design fails does it draw attention to itself; when it succeeds, it’s invisible.” It really wanted to hang with the other serifs, and now it does.

In search of ATypI

Published

This is the text of the talk I gave yesterday at ATypI 2019 in Tokyo, about the project I’ve been working on for the past year: a history of ATypI. A draft of the first part of the history is now available on Medium.

*

I’ve given this talk the title “In Search of ATypI” because it really did require a search, to uncover the Association’s early history.

The Association Typographique Internationale (ATypI) was founded in 1957. The driving force behind the creation of ATypI was Charles Peignot, managing director of Deberny et Peignot, one of the most important French type foundries. (This, incidentally, is the reason why the Association’s name is in French.) The first official general meeting of ATypI took place in Lausanne, Switzerland, during an exhibition called “Graphic 57.” The list of people involved in that first meeting is a virtual Who’s Who of the type world of the 1950s.

Over the 62 years of ATypI’s existence, we haven’t always been very good at keeping records and preserving the association’s institutional memory. Most of the records we have are now kept at the University of Reading, but those records don’t go back past the 1970s and a little bit of the 1960s. And only some parts of them have been organized and catalogued.

When the Board of Directors commissioned me last year to write a history of ATypI, I had to see if I could find some documentation for those early years, and try to talk to the relatively few people left whose memory goes back that far.

My own involvement with ATypI began in 1990, when I attended Type90 in Oxford, my first type conference. So I have several decades of first-hand knowledge; but when ATypI was born I was barely seven years old. On the other hand, in subsequent years I served on the Board of Directors for fourteen years and as President for six, I have written quite a lot about typographic history, and I’m willing to talk to pretty much anyone while I’m doing research. So it may be that I was the right person to ask to write this history.

I only wish we had begun this project ten years ago. But I suppose everyone writing a history of a contemporary organization has a similar regret.

*

There are many boxes and file cabinets of ATypI records at the University of Reading, and right after the 2018 conference in Antwerp, I spent several days in Reading digging into those boxes. Some of them were well organized; some were not. My work was made easier because Ferdinand Ulrich had done some organizing and cataloging of the materials as part of his postgraduate research at Reading, so I had Ferdinand’s very useful outline of what kinds of materials we had and where they were in the archive.

And by following up on a couple of serendipitous leads, I discovered earlier collections of papers from both Charles Peignot and John Dreyfus, co-founders of ATypI and the association’s first and second presidents, respectively. These were not in Reading.

*

The Peignot lead came from Jean François Porchez, who was ATypI president from 2004 to 2007, and who organized the 1998 ATypI conference in Lyon. I stopped over in Paris for a couple of days on my way from Antwerp to Reading, and over dinner, Jean François told me that he thought that Peignot had given his papers to the Librairie Paul Jammes, a highly respected rare-book dealer. This antiquarian bookshop is located in a very old building in the heart of Paris, in the Saint-Germain-des-Prés quarter of the 6th Arrondissement. The very next day, I visited the bookshop and met the director, Isabelle Jammes, the granddaugher of the founder. She was very helpful, but she told me that the Peignot archives had been donated many years ago to the Bibliothèque Forney, the city of Paris’s specialist library for, among other things, the graphic arts.

I had no time during my brief stopover to visit the Bibliothèque Forney myself, but luckily one of my American friends who lives in Paris is an art historian and editor, and she is also a member of the Forney. She was quite familiar with the library, she speaks French, and she was willing to go to the library and dig into the Peignot archive.

So I got permission from the Board to commission her to do exactly that.

It turned out that the Peignot archive, or “le fonds Peignot” in French, had an unusual condition attached to it: only items that had already been published could be photographed or scanned; original documents could not, although they could be quoted. This meant that Allison had to copy out by hand any information that seemed relevant.

Not all of the Peignot archive was concerned with ATypI, but among the papers were many records of early meetings when the Association was first being planned and when it first got going – the institutional memory that was missing from the archives in Reading. There wasn’t much personal correspondence, unfortunately.

*

But here is where the other unexpected lead comes in. One of the long-time ATypI members that I got in touch with was the Swiss book designer and publisher Erich Alb. Erich told me that John Dreyfus, the second president of ATypI, had donated four boxes of ATypI-related papers to the St Bride Printing Library in London many years ago, and recommended that I go find them.

When I got to Reading, I told Gerry Leonidas about this. I didn’t have time to go to St Bride’s myself, but Gerry of course is very familiar with the library and said he would visit it and see what he could find. A few weeks later, when he had a chance to do that, he discovered that the Dreyfus papers were indeed there, but that nobody had been aware of it. Apparently the four boxes had somehow been put into storage with their labels to the wall, so that they appeared to be just four more unidentified boxes in an already over-stuffed library.

What Gerry found in those boxes was exactly what we had been looking for: not just official documents but correspondence between John Dreyfus and other founding members of ATypI, including of course his friend Charles Peignot. There are missing pieces and blank holes in the historical record, but between the Dreyfus papers at St Bride and the Peignot papers at the Forney, we now have a fair amount of documentation describing how ATypI got started.

*

The impetus behind the creation of ATypI was the advent of phototypesetting, which Charles Peignot supported but which he thought would make it much easier for competitors to copy each other’s type designs. Of course, copying of designs goes back as far as the early 16th century, when the printers in Venice accused the printers in Lyon of copying their type designs. But it was a major feature of the type business in the first half of the 20th century, with each major foundry or type-machine manufacturer rushing out new type designs that would echo the latest popular designs of their competitors.

In those days, type was either set by hand or cast on a mechanical typesetting system. Those systems were not mutually compatible; each manufacturer made its own type that worked only on its own typesetting machines. Even if a foundry licensed one of its designs to a manufacturing company like Linotype or Monotype, the design would have to be redrawn and engineered to work on their system. (This was also true of the new phototypesetting machines.)

Peignot’s goal was to have type design included in the system of international standards that was governed by the Hague Agreement of 1925 on industrial designs. A large part of ATypI’s early effort was devoted to achieving this goal, including participating in endless international standards meetings and trying to establish ATypI as an expert voice on matters of type and typography.

As it turned out, all these efforts were for nought. The quest for international protection of type designs was a quixotic effort that, over the course of more than 60 years, has never fully achieved its goal. But that’s a story for a later part of the ATypI history project.

What ATypI did achieve, through the efforts of Charles Peignot, John Dreyfus, Jan van Krimpen, G.W. Ovink, and many others, was to bring the leading figures of the typographic community together, creating an international forum for discussion of type design and typography. When they started, they were thinking in terms of a “European Typographic Union,” which quickly expanded to become an “International Typographic Association,” including the United States and Canada. I wonder what the founders would have made of ATypI today, with our focus on education rather than industrial protection, and our expanded reach around the world. I like to think that they would approve.

*

So far, my research has been mostly about the earliest years of ATypI’s history, since those are the least known. But here are a few highlights from later years.

The 1967 ATypI Congress at UNESCO in Paris was the first to be a real conference, not just a series of business meetings. As Matthew Carter recalls: “Over time, people realized that this single question, the protection of typefaces, was not really going to be enough of a reason for ATypI to exist. So these annual conferences got more and more important in the life of ATypI. They became more social and less industry-oriented. That was a novel idea at the time, to have a program of talks and so on. As far as I remember, all of them since then have had a program, some degree of talks.”

In 1973, the early efforts at type-design protection culminated at the Vienna Congress, which was a general effort at revising international standards for the protection of industrial designs. A special agreement about type design was reached, and hopes were high; when John Dreyfus concluded his term as President later that year, he did so with a feeling of “mission accomplished.” But that turned out to be premature. The agreement required at least five countries to ratify it. In the end, only two countries did.

In addition to its conferences, ATypI sponsored a series of “working seminars” between 1974 and 1992, each one focusing on a particular aspect of type or typography. (As you know, a new series of Working Seminars has just been launched, beginning with the one in Colombo, Sri Lanka, earlier this year.) The 1983 Working Seminar at Stanford University, “The Computer and the Hand in Type Design,” turned out to be a seminal event, focusing attention on the new possibilities of digital typography. It was organized by Chuck Bigelow, who at the time was an Associate Professor of Typography at Stanford, and featured, among others, Hermann Zapf, John Dreyfus, Donald Knuth, and Jack Stauffacher.

Type90, the 1990 conference in Oxford, England, was ATypI’s first event to be open to the wider community of visual design. It was organized by Roger Black, and it was a typographic extravaganza, presenting both the traditions of type and the effects of new digital technology. Sometimes it turned into a clash of cultures: I remember the shock with which some people reacted to Zuzana Licko’s all-digital presentation with its rock-music soundtrack, in one of the hallowed halls of Oxford. From that date on, ATypI was more outwardly focused than it had been in its earlier days.

In 2009, ATypI held its first conference in Latin America, in Mexico City. In 2015, the first ATypI conference in South America was held in São Paulo. The first ATypI conference in Asia was held in Hong Kong in 2012, and now here we are in Tokyo for our second Asian conference.

*

We have just published a draft of the first part of my history of ATypI on the ATypI website, so you can go there and read it now. It’s just a draft; it will be part of the first book in the ATypI history series, which will be published in time for next year’s conference in Paris. I welcome comments and any new information from anyone who was involved in ATypI’s early years. I would be especially happy to hear from anyone who has usable images from those early years; what we have is pretty sparse.

Thank you for your attention. I hope this short talk has given you a bit of historical context for the ongoing project that is ATypI.

Reading Le Guin

Published

A few months back, I got the second two-volume set of Ursula K. Le Guin’s work in the Library of America, “The Hainish Novels and Stories.” (She is one of the very few writers to have their work published in the Library while still living.) Since then, I’ve been rereading these stories, or in a very few cases reading them for the first time. All of Le Guin’s fiction, even the earliest work, stands up to rereading; that’s one of the things I value about it. Her sensibility and her care for language have spoken to me from the moment I first encountered them, when I happened upon Rocannon’s World on the revolving wire paperback rack in a stationery store. (The book was an Ace Double, back-to-back with Avram Davidson’s The Kar-Chee Reign.)

As I read through this collection, I thought about how much the late Susan Wood would have appreciated it. First of all, Susan would have been delighted to see Le Guin’s work in the Library of America. Even more, though, I think she would have appreciated the later stories. Before Susan’s death in 1980, I can remember her lamenting that Le Guin had yet to write “the Hainish novel”: that is, a novel about the Hainish themselves, from their own perspective, not just about the many cultures that their ancestors had spawned. While Le Guin may not have written quite what Susan was anticipating, she did come back, after a gap of several years, to write a series of late stories that delved ever deeper into the culture and psychology of the Hainish and their interaction with the rest of humanity.

Susan and I both met Ursula at the same time, in August 1975, in Melbourne, where both Ursula and Susan were guests of honor at the first World Science Fiction Convention to be held in Australia. Later, Susan edited Le Guin’s first book of essays, The Language of the Night. Susan was a passionate scholar and an enthusiastic teacher. (At the University of British Columbia, and at earlier universities where she had taught, she created courses on science fiction and Canadian literature – both of which were looked on skeptically by the English department and both of which brought in large numbers of enthusiastic students.) Her introduction to Language of the Night was a major essay that she worked long and hard on, situating Le Guin’s writing and presenting it afresh to a thinking audience.

It’s entirely possible that, had Susan lived, she would have been the one to write the introduction to Le Guin’s Hainish novels and stories for the Library of America. I like to think so.

When I first started reading that volume, last winter, and started musing about how much Susan would have enjoyed it, I thought I ought to mention it to Ursula. She would appreciate it, I was sure. But I was slow to act; Ursula had been in poor health, and in January she died. I never managed to share that particular insight.

In June, I had the bittersweet pleasure of attending the celebration of Ursula’s life, in Portland, Oregon. It filled the magnificent Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, and after a star-studded program of appreciations, ended with a dragon parading up onto the stage and then out into the street. Her long-time home town certainly knew how to celebrate Ursula K. Le Guin.

Sam Hamill

Published

Sam Hamill would have turned 75 on May 9. He had planned to celebrate his birthday with a publication party for his final book, After Morning Rain, on May 15, but in the end he realized that his health wasn’t going to last long enough to do it. Sam died a month before the planned event. It went ahead, however, on a more informal basis, as a remembrance and celebration of Sam and a welcome for his last book.

I’m now reading that book. I’ve been reading it slowly, parceling out the poems, making it last. It’s filled with little gems, of feeling, observation, appreciation, lament – the distilled sensibility of a poet at the end of his life. Sam always felt that he was in conversation with the great poets of the past, especially those of ancient China and Japan; some of the poems in After Morning Rain explicitly echo that:

Coming to It

A midnight cup of sake,

a strange solitude.

Is this all I’ve become?

Old and alone, bending

over a poem

written in loneliness

by some old Chinese

bag o’ bones

more than a thousand years ago.

The book is a small, beautiful volume, designed by and with a cover painting by Ian Boyden.

Sam was an evocative, insightful, lyrical poet, like his mentor Kenneth Rexroth. He was also, like Rexroth, a world-class curmudgeon. There’s bitterness, but also love, in Sam’s last poems. He transcended his own life through his work and his art.

Sam was an exacting and generous editor, and that’s where his greatest influence may lie. He co-founded Copper Canyon Press and was editor there for nearly thirty years, bringing innumerable books of fine poetry by greats and unknowns into print in the United States. That has been an important part of our cultural life.

I’m not sure when I first met Sam, but I came to know him when Loren MacGregor and I were publishing the short-lived Pacific Northwest Review of Books in 1977 & 1978. Sam was enormously helpful and encouraging to us in our efforts. I well remember the interview with Sam and his then-partner Tree Swenson that was conducted and submitted to us by a new writer; when we showed Sam the draft, he exclaimed grumpily, “I speak in paragraphs, dammit!” and insisted on correcting it – to the great benefit of our readers.

I’ve had the pleasure of designing several of Sam’s books, beginning with Passport, a collaboration with the artist Galen Garwood, which was published by Broken Moon Press in 1989. I’ve designed books of essays by Sam (Basho’s Ghost, A Poet’s Work) and poetry (Destination Zero). I always tried to give his work the typographical clothing that it deserved.

In 1993, I got a call from Sam, out of the blue. “Would you like to help me design a book?” He and Tree had just split up, and she had been the designer of Copper Canyon’s books. That early casual-sounding request led to my designing all of Copper Canyon’s books and collateral for the next five years (and several more at various times after that). As I said at the time, I was trying to live up to the standards that Tree had set, making each book recognizably a Copper Canyon book while letting each one take its own form and shape. And I was trying to maintain Sam’s vision with each book, often working with paintings that he had chosen for the covers. I like to think I succeeded reasonably well. I felt that those were books that would be worth reading a hundred years from now.

Ars longa, vita brevis.

[Images, top to bottom: After Morning Rain, designed by Ian Boyden; Sam Hamill; Destination Zero, designed by John D. Berry; Sacramental Acts, Kenneth Rexroth, designed by John D. Berry.]

More writing

Published

I have just added a couple of complete essays to the rather minimalist “Writing” page on this site, and links to several others.

That page has so far consisted of short, and I hope intriguing, excerpts from various longer pieces of my writing. Now I’ve added links to almost all of the originals, making this a sort of landing page or entry point to these essays.

I’ve added the introduction to Contemporary newspaper design (2004), where I attempted to look at the development of newspaper typography over several technological and economic revolutions, and “The Business of Type”, my account of the origins, development, and demise of U&lc, which was the introduction to U&lc: influencing typography & design (2005). Both of these were books that I edited for Mark Batty Publisher; both of them are now out of print. I think those essays are worth making available again.

I’ve added some more links, too. Check ’em out.

[Update, April 15, 2016:] I’ve now added the missing piece, the preface to Language Culture Type. It is a less substantive piece than the others, but still worth having intact.

Translated serifs

Published

My little book Hanging by a serif caught the eye of Bertram Schmidt-Friderichs, co-owner of Hermann Schmidt Verlag in Mainz, Germany, a fine small publishing company that specializes in books about typography and design. As a result, my book has been translated, revised, and slightly expanded, and is about to be published in Germany. The German title is Thesen zur Typografie (the someone whimsical “Hanging by a serif” proved resistant to translation), and its release coincides with the annual Frankfurt Book Fair, which opens today.

I haven’t held a copy in my hands yet, but I know it has a sewn binding and two-color printing – more ambitious than my original self-published edition. And a few different serifs. Perhaps it will see a more ambitious American edition, too.

Thesen will join other new books in the Hermann Schmidt line at their display at the Book Fair this week.

Sprinting into the future

Published

My e-book essay “What is needed” has just been republished on the website of “Sprint Beyond the Book,” a project of Arizona State University’s remarkable Center for Science and the Imagination.

In May, Eileen and I met up with nine other invited guests to participate in CSI’s third “Sprint” event, a workshop/conference focusing on “The Future of Reading.” CSI’s first Sprint, with a theme of “The Future of Publishing,” had taken place last fall at the Frankfurt Book Fair, where the participants worked in the midst of the hurly-burly of the world’s biggest book festival; the second (“Knowledge Systems”) took place in January on CSI’s home turf at ASU. This third one was held at Stanford University, in conjunction with Stanford’s Center for the Study of the Novel.

The mix of people and ideas was invigorating, and the fruits of that brainstorming are intended to be published. (One description of what the Sprint was all about was “creating and publishing a book in three days.” But what kind of a book, exactly?) The other participants at the Stanford event were Jim Giles, Dan Gillmor, Wendy Ju, Lee Konstantinou, Andrew Losowsky, Kiyash Monsef, Pat Murphy, David Rotherberg, and Jan Sassano. The whole project was organized by its instigator and ringleader, Ed Finn, and his talented and indefatigable staff members Joey Eschrich and Nina Miller. I’ve been working with Nina, when we each have time, on the format for eventually publishing the results of the Sprint.

In the meantime, in somewhat kaleidoscopic form, parts of our conversations and digressions, and the texts that we created in the course of the three days, are available now on the “Sprint Beyond the Book” website.

“What is needed,” which I wrote more than two years ago as a post on this blog, is essentially a high-level technical spec for the missing tools that we need in order to do good e-book design. Most of these tools are still missing, two years later, despite the rapidly changing nature of digital publishing. Some of the ideas have made their way into various proposals for future standards, but not much has been reliably implemented yet. I’m still looking forward to the day when everything I was asking for will be so common as to be taken for granted. Then we can make some really good e-books; and our readers will be able to enjoy them.

Questionable practices

Published

Many of you know that I live with an author: my partner and wife Eileen Gunn is a well-respected short story writer, whose first collection, Stable Strategies and Others, was published in 2004 by Tachyon Publications. Not surprisingly, I designed and typeset that book (and ended up doing a good bit of design for Tachyon, sometimes covers, sometimes interiors, over several years). We also developed a visual identity for the book and its marketing campaign – a necessity in today’s publishing world – where I had fun putting the incendiary cover image to work in other contexts.

Now I’ve designed her second collection, Questionable Practices, which will be out in April from Small Beer Press. The interior text design echoes the earlier book, but we gave this one a distinctly different cover design – though one that I think will sit comfortably on a bookshelf next to Stable Strategies. The publisher has just sent out ARCs (Advance Reading Copies) to reviewers.

The cover for Questionable Practices went through three entirely different versions, as these things often do (not counting the innumerable iterations of each still lurking on my hard drive). It’s in the nature of commercial book publishing that the publisher needs a cover image, for publicity and marketing purposes, long before they need a finished book; indeed, often enough the text isn’t finalized until long after a cover image has been widely distributed. When I was working as a typographer at Microsoft Press in the mid-1980s, we used to get outside “designs” from a local studio that simply provided cover sketches and sample pages with typical interior design elements; these were done long before the book was even written. Not only did we have to execute the final covers, but we often had to invent designs for new interior elements that came along as the books were written and edited. Eventually, since we were doing half the design work anyway, we took the interior design in-house.

Eileen’s stories don’t fit into obvious categories; they’ve almost all been published as science fiction, but she refuses to ever repeat herself, and her work rejects easy classification. When I designed the cover for her first collection, I was trying to do something that would stand out both on the general-fiction table and in the science-fiction section of a bookstore. As I discovered, though, few bookstores were willing to shelve copies of the same book in two different sections; it was always one or the other. Today, with online marketing and bookselling, perhaps it’s easier to place a book in multiple categories at the same time. In any case, today a book cover needs to be clear and work well as a little thumbnail image, not just at full size on the physical book.

Naturally, each of the three cover versions for Eileen’s book seemed perfect to me at the time, but in the end the one you see at the left worked best – and will be on the book. As a completely objective and nonpartisan observer, I can say: watch for it.

[Update, Jan. 16: I just sent the book to the printer today. Publication date: March. Typeface: Dolly Pro.]