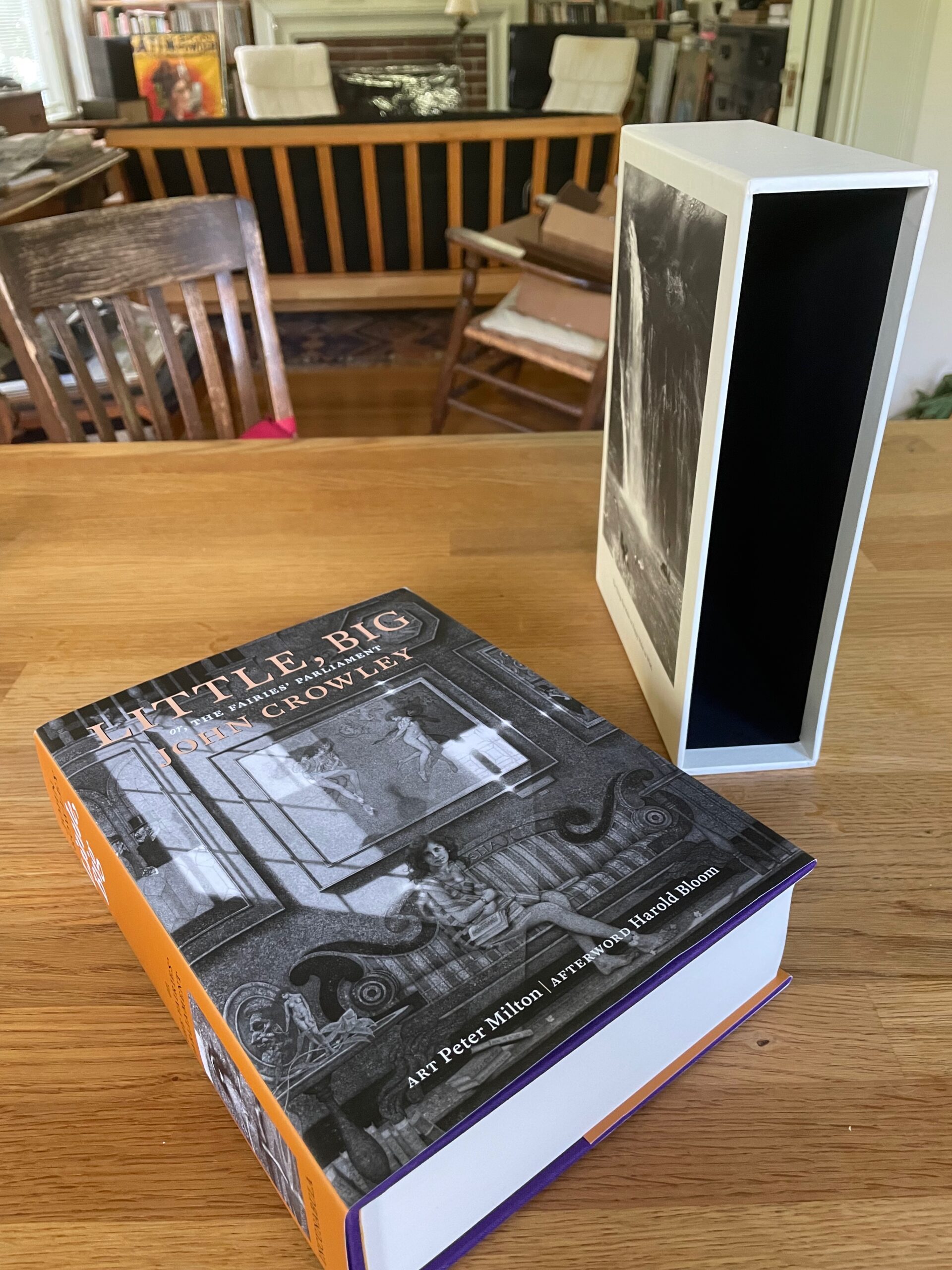

Its origins are lost in the mists of time. Ron Drummond, the one-man publisher of Incunabula, reminds us that he first broached the subject to John Crowley thirty years ago: the subject being a special, celebratory edition of Crowley’s well-loved novel, Little, Big (1981). Incunabula had already published one book by John Crowley and two by Samuel R. Delany, of which I had designed two: Crowley’s Antiquities (1991) and Delany’s Atlantis: Three Tales (1995).

Incunabula, which Ron had named in a combination of respect and chutzpah, was a small press that published worthwhile literary works of science fiction and fantasy (or fantastika as critic John Clute calls it). “Incunabula,” which means “cradles” or “swaddling clothes” in Latin, is used to refer to European printed books published before the year 1501. By that time, sixty years after Gutenberg’s innovations, printing had exploded from a craft into an industry, and many of the standards of book design that we still follow were well established. In calling his new press Incunabula, Ron was drawing on a very long tradition.

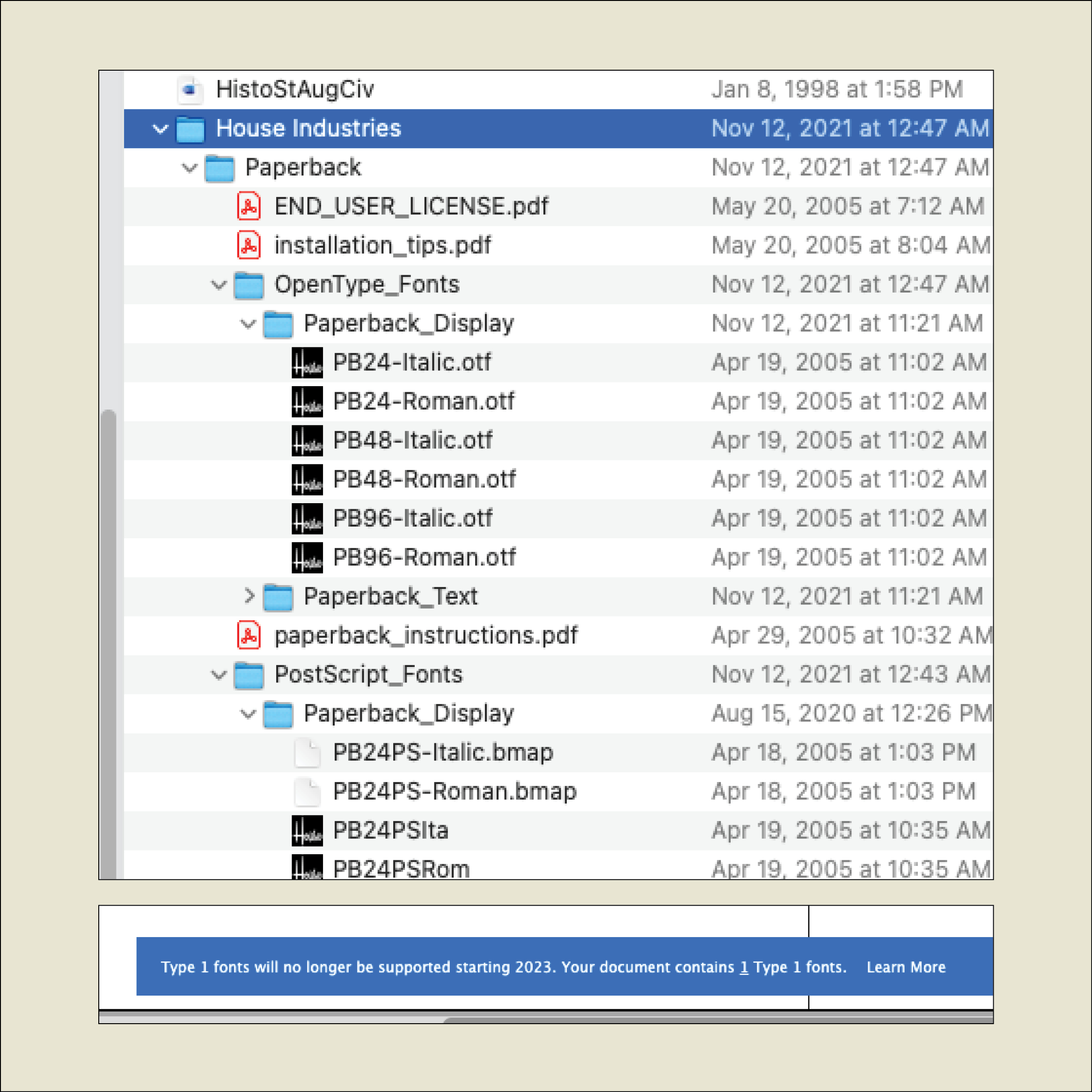

I have no recollection of when it was that Ron first asked me about designing this more ambitious volume. I can find files related to the project dating back to 2003, and my earliest design file, LB design 1.indd, is dated May 9, 2005. I’ve been working on this book for at least seventeen years.

I have often referred to it as “Zeno’s book project,” for the way it seemed to keep approaching completion without ever quite arriving. I have also sometimes called it “the Oxford Lectern Little, Big,” in reference to Bruce Rogers’s monumental Oxford Lectern Bible. Our book, however, is not so monumental as to require a lectern.

The tale of how this book came to take its final form, with an intricate interweaving of original etchings and engravings by the artist Peter Milton, would take too long to tell. It has its painful interludes. Ron’s ambitions didn’t always correspond with his practical abilities, or with his never-robust health; this was a much bigger project than any he had undertaken before. But his vision was always clear: choosing and framing details from Peter Milton’s art that would create a conversation with the text of the novel.

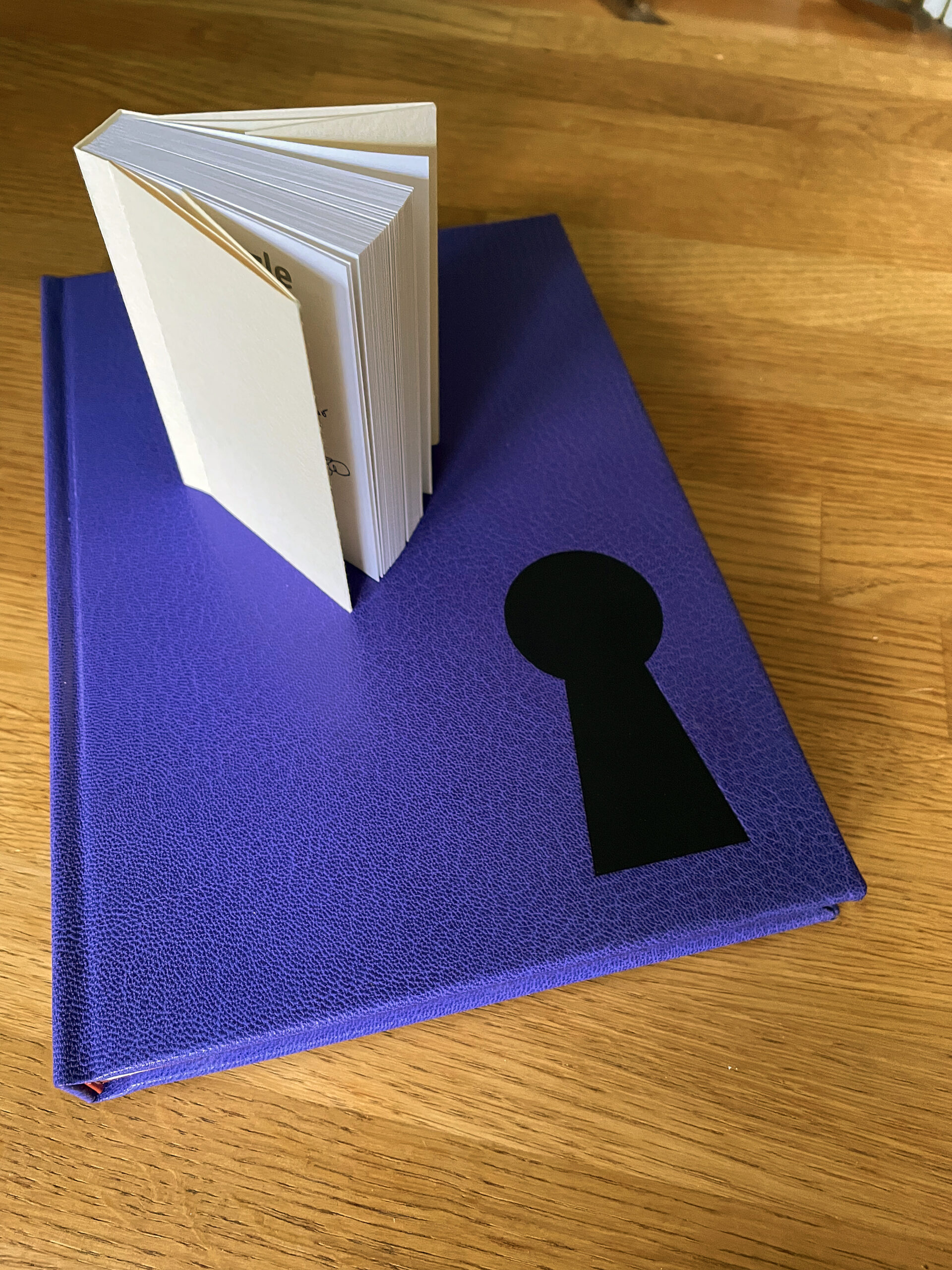

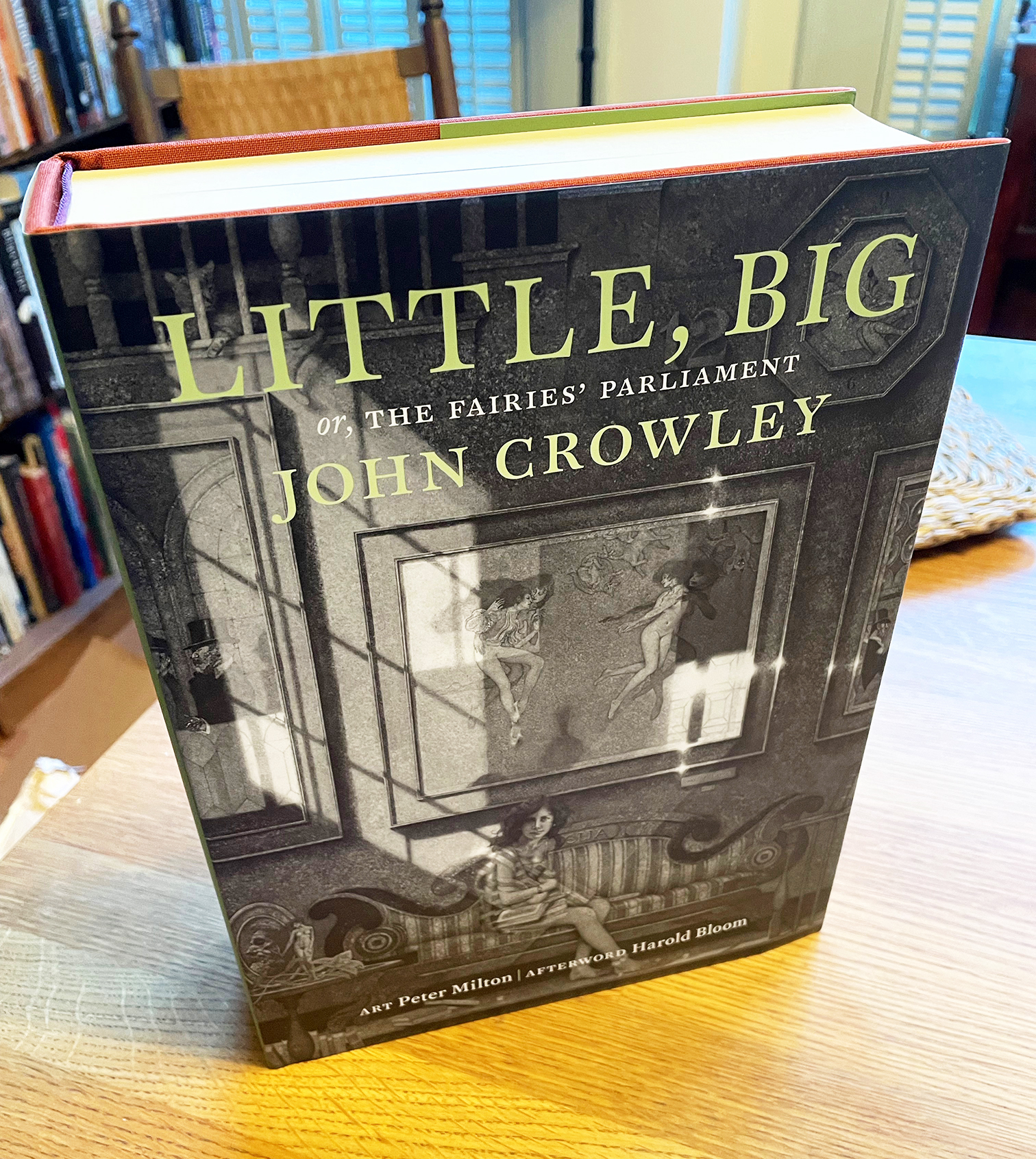

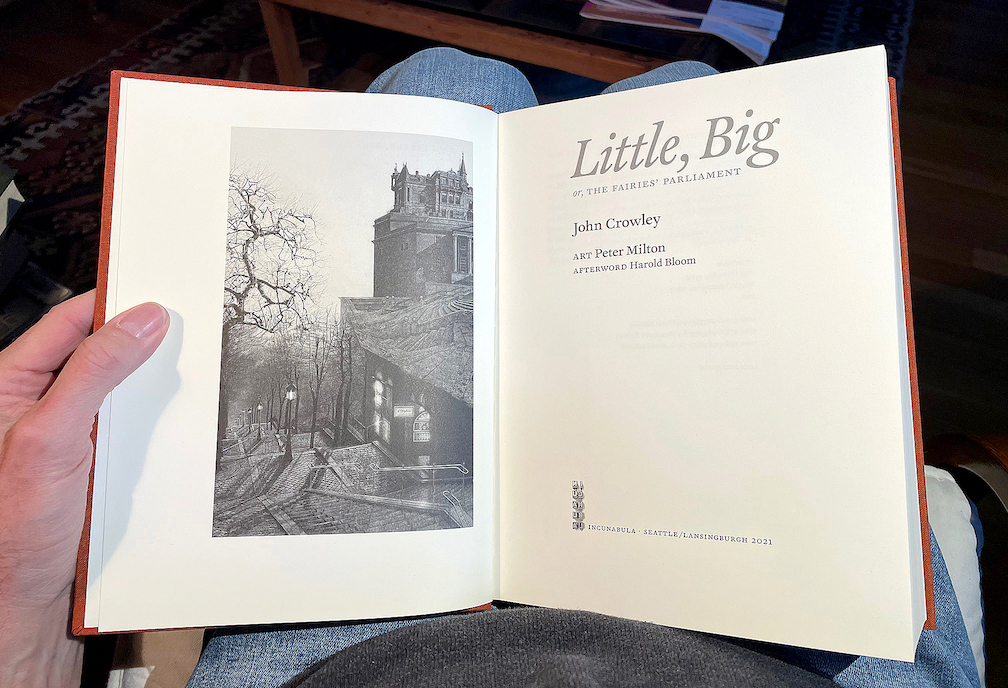

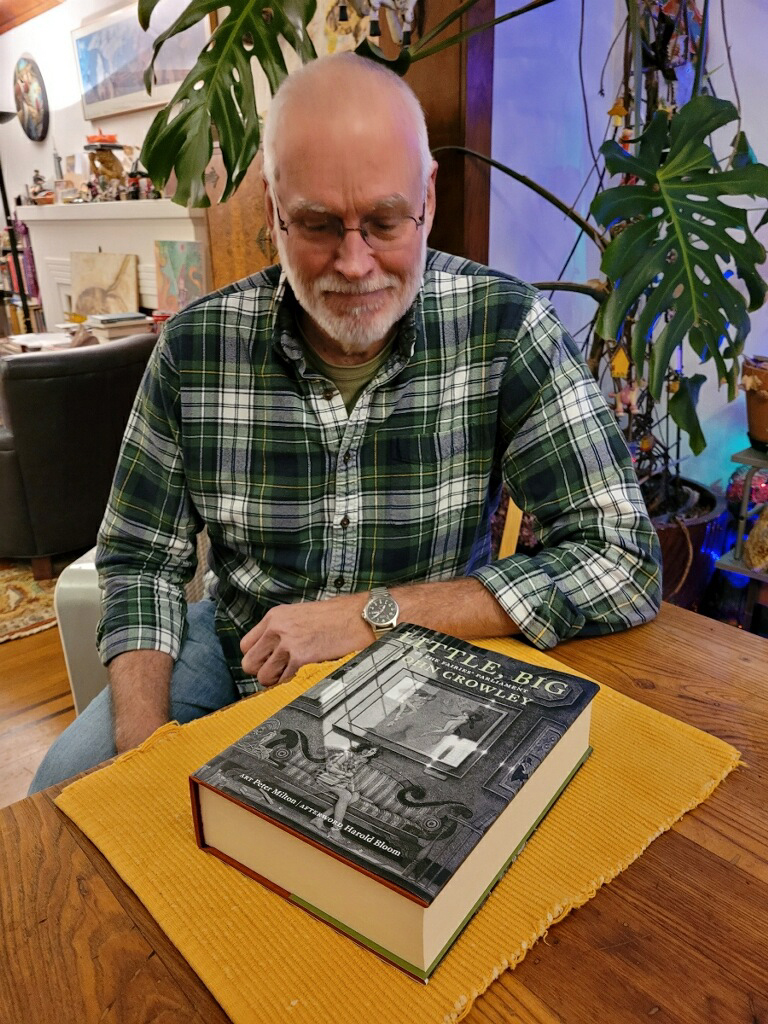

Now, amazingly, Zeno’s arrow has hit its target. A couple of weeks ago, my advance copy of the trade edition arrived in my hands, a few days after Ron’s copy reached him. It’s an 800-page tome, 7½ x 10 inches, sewn in signatures, printed on luxurious Mohawk Superfine paper, rich with art, and all digitally typeset in Akira Kobayashi’s historically inspired typeface FF Clifford. I can say, having hefted the book and laid it in my lap and begun my own rereading of a favorite text, that it’s everything I had hoped for: comfortably readable pages, beautifully printed images, in a sturdy yet flexible binding. The printer, Brilliant Graphics in Exton, Pennsylvania, did a masterful job.

Fulfillment will be handled through Dallas-based literary publisher and distributor Deep Vellum. There are still copies of the trade edition available for purchase. The 25th anniversary edition of Little, Big, which is now the 40th anniversary edition, is finally a reality.

Categorized as book design, books, culture, printing, publishing, typography, writing & editing |