Two weeks ago I got back from the 2025 ATypI conference in Copenhagen. This was the first time ATypI had gone to Copenhagen since the 2001 conference – which took place just two weeks after 9/11. As you can imagine, being an American in Denmark in those two years had quite different resonances. In 2001, before George W. Bush turned an atrocious crime into a misguided war, the reaction of people abroad was aghast sympathy. This year, the people I spoke with in Copenhagen mostly offered wry commiseration, along with lots of questions. (There was one Persian taxi driver who had a good knowledge of U.S. politics and with whom I had a fascinating conversation on the way from hotel to conference venue.)

The conference was held at the Royal Danish Academy (Det Kongelige Akademi – Arkitektur, Design, Konservering), in buildings that had once housed part of the Danish Navy. The lead local organizer was Sophie Beier, who teaches at the Academy and heads up its Centre for Visibility Design (and has spoken many times at previous ATypI conferences about legibility and readability). This year there were two tracks of programming, in two separate spaces in the same building – the same building, but you had to go outside to get from one to the other. As at most events like this, you finally figure out how to get around and how to find all the places you need to be just before the event ends – and that hard-won information is stuck in your memory with no possible future use. I can say that if you got dropped off at the Academy’s address by a taxi or Uber, it would take you a while to find the entrance to the conference. But people at the Academy were quite willing to direct you.

One thing that had struck me when I first looked at the program and the list of speakers was that most of the names were not familiar to me. That could be disconcerting but was mostly encouraging; it means that the Association is not mired in old habits but open to new people and new ideas. Indeed, a large number of the talks were unrelated to traditional European typography and type design; there were even, on the last day, two different talks about aspects of Chinese type scheduled opposite each other. (Okay, that might be excessive; I would have liked to listen to both.) I am not a fan of multiple tracks of programming, since you always have to choose one or the other, but the organizers this year were very good at keeping the two schedules coordinated and giving people ample time to move between the two tracks at will.

And what did people talk about? Oh, you know, the usual: type, typography, reading, publishing, various scripts, technical underpinnings of typesetting and type design. Just to give you an idea of the range, here are the first two talks, which were on opposite each other on Wednesday morning: “Knud V. Engelhardt, a Danish Typographic Pioneer” and “Streamlining and Flexible Traditional Chinese Type Design with Open-Source Character Set.”

There were several talks on fonts for African languages, and a panel discussion of designing for the Arabic script in different countries, Arab and non-Arab. Niteesh Yadav’s talk on “Typography as a Living Medium,” about adapting text for use in Augmented and Virtual Reality, particularly caught my attention: what he said seemed like a logical extension of the concerns I’ve been involved with for several years for readable typography for the screen. (I asked Niteesh to write something for the Scripta Typographic Institute site, which I’ve let languish for far too long. The conversation could use a refresh.)

It’s never possible to see everything and talk to everybody. In the interests of my ATypI history project, I had lunch with the organizers of the previous Copenhagen conference, Henrik Birkvig and Torben Wilhelmsen, and quizzed them for their memories, with my trusty voice-recording phone turned on. A number of people offered new information about past conferences, some from personal memory and some from knowledge of older documentation. (I’m working on the chapter about the 1960s now, and it’s going to be a work in progress, as I try to fill in the holes in the fossil record.) On the first days, when the weather was unwelcoming, the only place to foregather easily was the relatively small hallway outside the main auditorium with its excellent coffee bar; but when the weather improved and the sun came out, people would spill out onto the grass, which was also where various demonstrations were set up under a tent. Apart from the coffee bar and a cafeteria, the options for meals required a bit of a walk, but there were some water-side restaurants and a popular outdoor food court not far away.

The Poles managed the conference’s infrastructure brilliantly. The Finns and Brazilians got me into late-night trouble with unending parties. The Chinese got us all talking about hanzi. The Danes, of course, welcomed us to their country and their typographic traditions. I enjoyed both social and intellectual interaction with people from Australia, Britain, Germany, India, Lebanon, Poland, the Netherlands, Argentina, Portugal, Austria, and even the USA. That’s one of the pleasures and also the values of an ATypI conference.

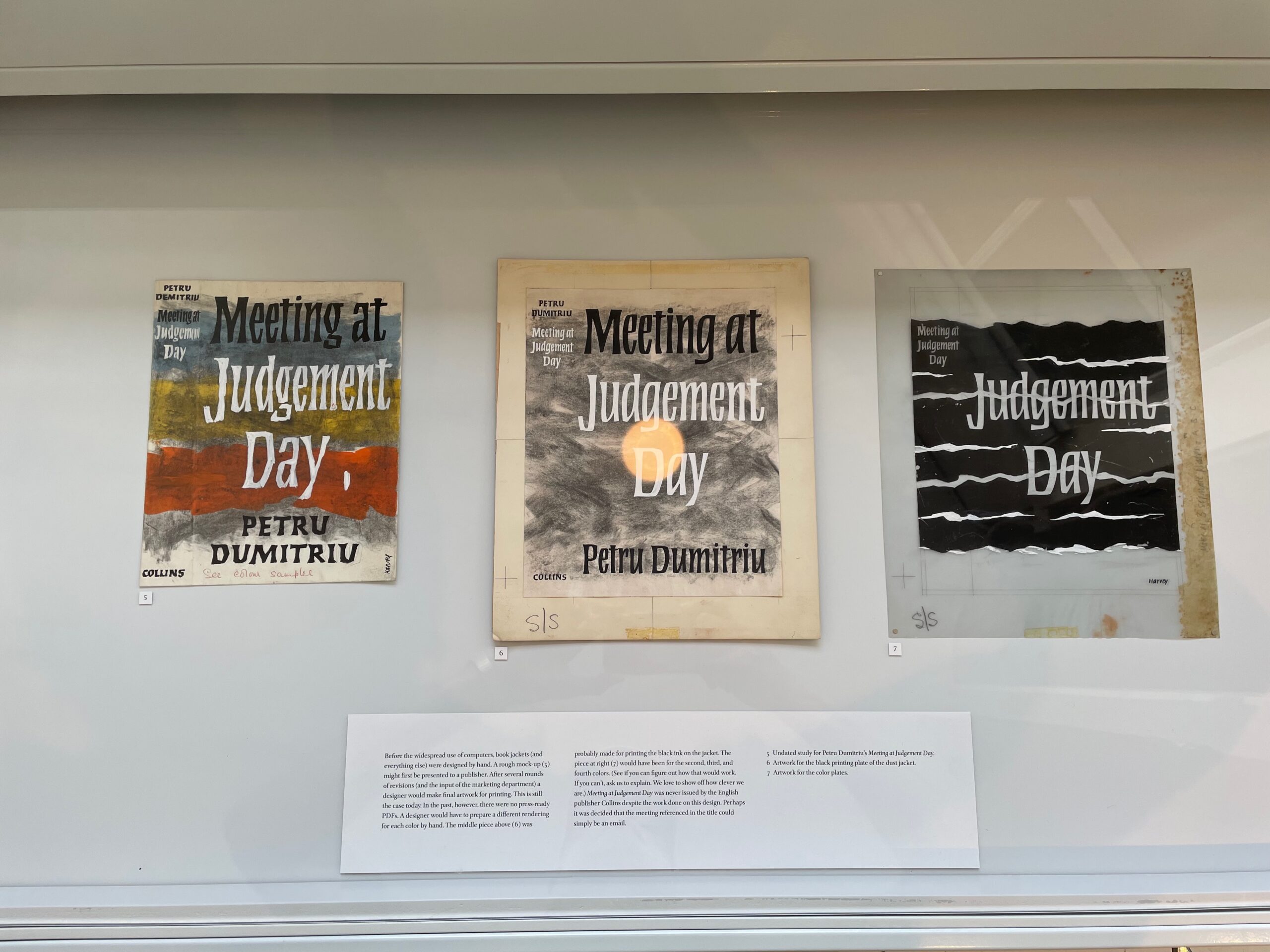

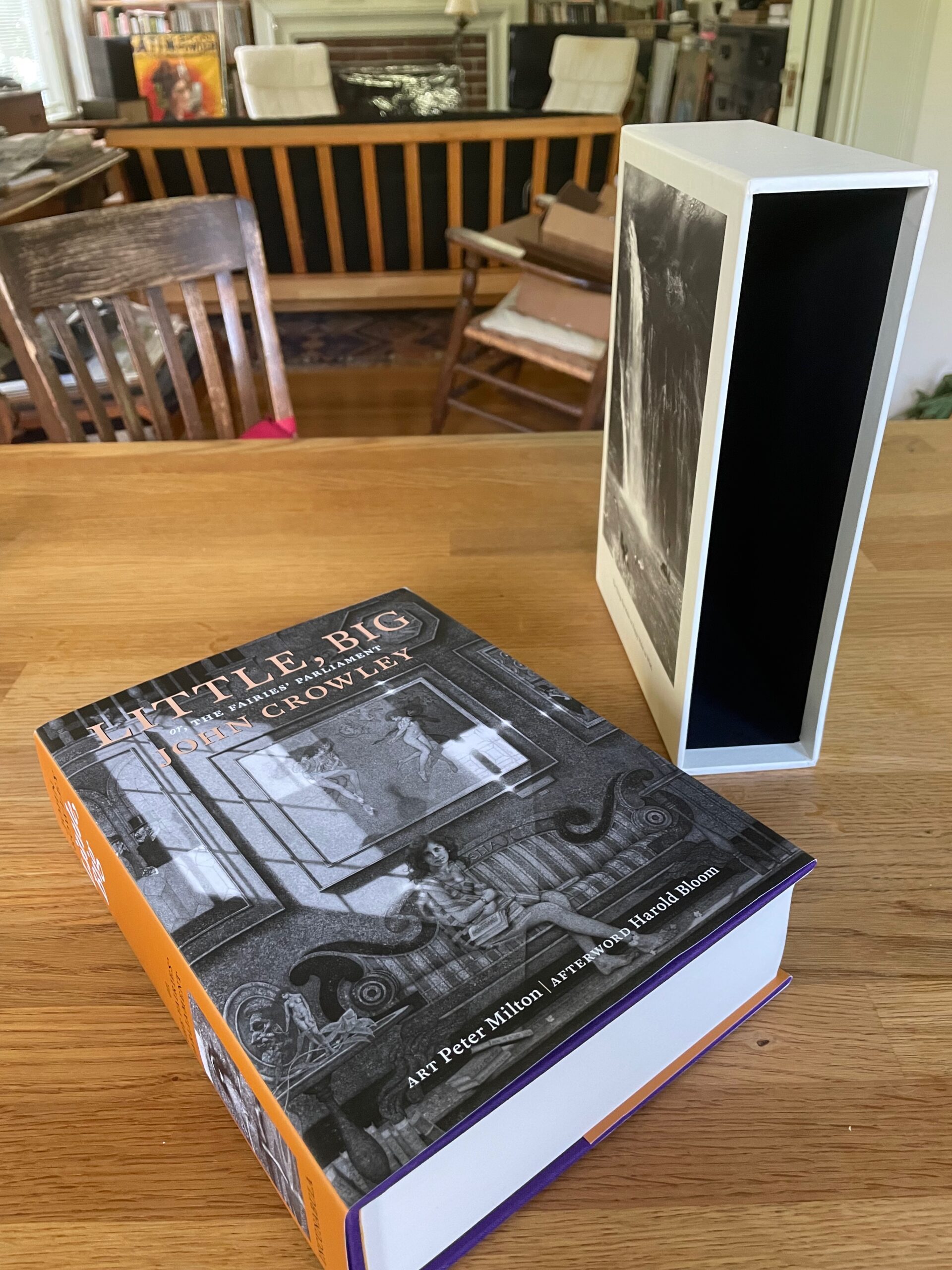

[Above: attendees at the official reception in Copenhagen’s ornate City Hall; the building at the Royal Danish Academy where the ATypI program took place; Taurai Valerie Mtake on “The future is ancestral.”]

Categorized as events, people, type history, typography |