When a new publisher at Microsoft Press began undermining the craftsmanship we had been trying to bring to computer-book publishing, I rattled the cage before making my escape.

When founding publisher Nahum Stiskin announced that he was leaving Microsoft Press, it was obvious to all of us that this was the end of an era. In a sort of “my work here is done” memo, Nahum explained that he was a “start-up kind of guy,” that he felt he had successfully gotten the Press on its feet, and that it was time for him to move on to something new. Whether all this was true or whether it was a face-saving fiction — whether Nahum really jumped or was pushed — we were never sure.

In any case, the directors found themselves interviewing likely candidates for the new publisher. They were remarkably transparent about this; although neither Microsoft nor Microsoft Press was in any sense democratic, they solicited input on their short list from the rest of the staff. The top contender seemed to be a man named Min S. Yee. He had an intriguing background — he himself was part Chinese, part Native American, and he had been among other things

For his first month as Publisher, Min sat back and listened. He brought in several other people with him from his previous job, but that wasn’t immediately obvious as a bad thing. It was only after he had settled in and figured out the lay of the land that he let the hammer fall.

In one fell swoop he fired both the head of the art department, Nick Gregoric, and the head of the type department, Chris Stern. In Chris’s case, he had just come back to the office after a vacation, expecting to get back to work; instead, he was told to pick up his stuff and leave the building right away.

Min then installed his own people in those positions, people who had worked with him at his publishing company. Inevitably, they became known to the rest of us as “Min’s minions.”

As I recall, it was a bit later that Min decided that having two proofreading departments — an editorial proofreading department and a production proofreading department — was redundant, and laid off everyone in the production department. But those two departments had very different functions: one was concerned with the content, the writing, ultimately the manuscript that would be sent for typesetting and layout; the other focused on making sure that the typesetting and layout were done right and that nothing had been missed at the last minute. They were not, in any sense, redundant.

I recall the day when that particular chicken came home to roost. With no production proofreading department, a chapter of one of our books went from typesetting to paste-up and then got sent simultaneously to the editor and the author, which was the normal procedure. Only when the author called up fuming and upset did anyone realize that the entire chapter had been set in small caps.

The way the CCI typesetting system worked, you would insert a code in the text stream to begin setting small caps, and then you would insert another code at the end of that bit of text to turn off the small-caps command. Someone had failed to include the “turn off” code, so all the text from that point on got set as small caps.

This must have been obvious to the folks in the paste-up department. They could hardly have failed to notice. But this was after Min had summarily laid off both the head of that department, whom everybody liked, and the entire production proofreading department. So when the galleys came in, they simply pasted them up as usual, no matter what they looked like. (This was still in the days when digital galleys got output on photo paper, then cut up and pasted down on physical “boards,” cardboard sheets with layout grids printed on them in non-photo blue ink. That was what got sent to the printer. We had often been told to “tackle the FedEx guy” in order to get a last-minute shipment of paste-up boards to the printer on deadline.)

It was a fiasco — and a fiasco entirely attributable to Min’s reckless decision to get rid of the production proofreading department. I’m sure I was not the only one to laugh silently to myself when I heard about this.

You may guess that I was not happy with any of these changes. I was also fearless, or terminally foolish, and unwilling to submit to the expectations of corporate practice. With the press taking what looked to me like a disastrous and grossly unfair direction, I spoke up.

I wrote a memo. And I put a printed copy in everyone’s mailbox.

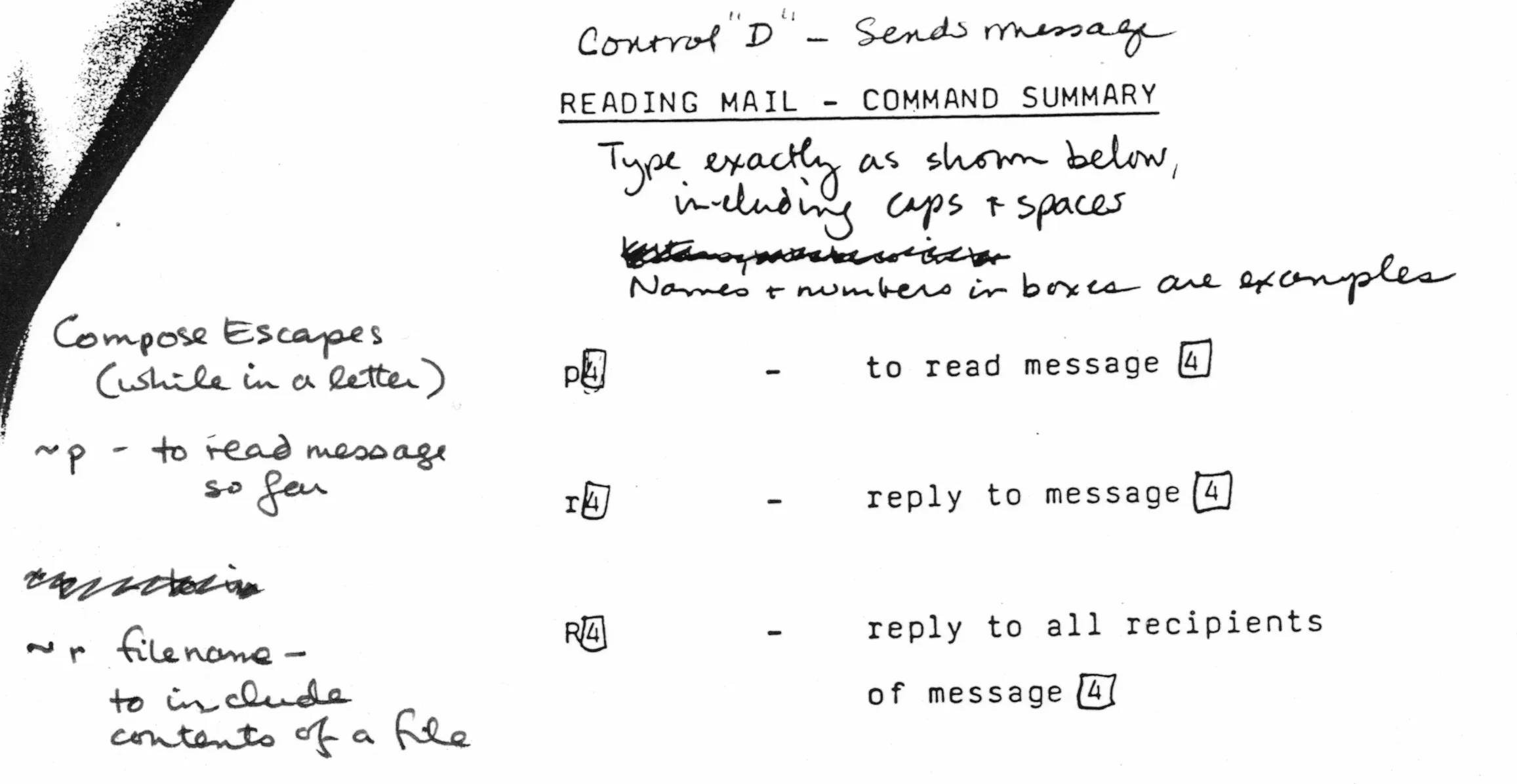

(Yes, email did exist, at least within the company. But it was at the level of rubbing two sticks together to start a fire. Think I’m kidding? This is a detail of the sheet explaining how to use Microsoft’s internal Xenix-based email system in 1984:)

I wish I could quote the memo that I sent. I know I still have it somewhere. It was forthright and righteous and too long and probably obnoxious, laying out what I thought was being done wrong and what ought to be done to create a new direction for the Press.

You can imagine how well that went down. For the occasion, Min and my new supervisor (also named Chris) invented a category that Microsoft had never had: they told me I was “on probation” as an employee. And nothing, of course, changed in the overall structure of how the Press was doing business.

I could have simply quit, at that point, but I decided that I wanted to finish the projects I was working on and continue to collect a paycheck for a while. Eileen was also planning on leaving Microsoft, and we decided that once we had both become unemployed we would decompress by taking a six-week trip to southern France and northern Italy in the fall.

Ironically, that fall was when Microsoft began offering stock options to all its employees, not just the upper management. The very day that my supervisor told me I was no longer on probation and had to offer me my first stock options, I got the pleasure of telling him: “No thanks, Chris, I’m leaving at the end of the month.” (It’s just as well that we had no idea what those stock options would eventually be worth.)

I could have applied for a transfer to another department within the company, but none of them held any appeal for me. It was publishing that I was interested in, not computer software. So I gave notice instead.

But it soon turned out that there was still work for me, if I wanted it, and I ended up coming back on a freelance basis to help out with occasional production proofreading. (There being, ahem, no longer anybody on staff to do it.) So I happened to be on campus, proofing galleys in a little cramped closet because there was nowhere else to sit, on the day that everyone’s next six-monthly bonuses were paid. That day, with their bonuses in hand, three of the Press’s directors resigned, as did several other Press employees. It was gratifying, though coincidental, for me to be there to see it happen.

[Copyright 2020. Originally published in Medium.]