ATypI’s Code Moral (Moral Code) was an attempt to establish a set of ethical guidelines for the design, marketing, and manufacture of typefaces. It was meant to be agreed upon and put into practice by all members of the association.

Purpose of the association

The whole reason that Charles Peignot proposed the establishment of an organization like ATypI in the first place was to advocate for legal protection for the designs of typefaces, and to prevent or discourage unauthorized copying of designs by competing type foundries.

Even before the official establishment of ATypI in 1957, Peignot had written to Maitre (Me.) Guido Poulin, the lawyer he had engaged to work with him on this, asking Poulin to give him his opinion on two questions: whether such an organization would be useful in getting the countries that had signed on to the Berne copyright convention to include type design, and whether he thought that an international association “exercising the same profession in all the countries of the world” would carry weight by asserting its moral authority on the question.

The answer was clearly yes, and Poulin was the spearhead of ATypI’s legal approach for several years. Whether he was the right person for the job eventually came into question, as the efforts dragged on over years and Poulin’s fees mounted; some members of the Board questioned his understanding of international industrial law. But Poulin remained the point man for the project.

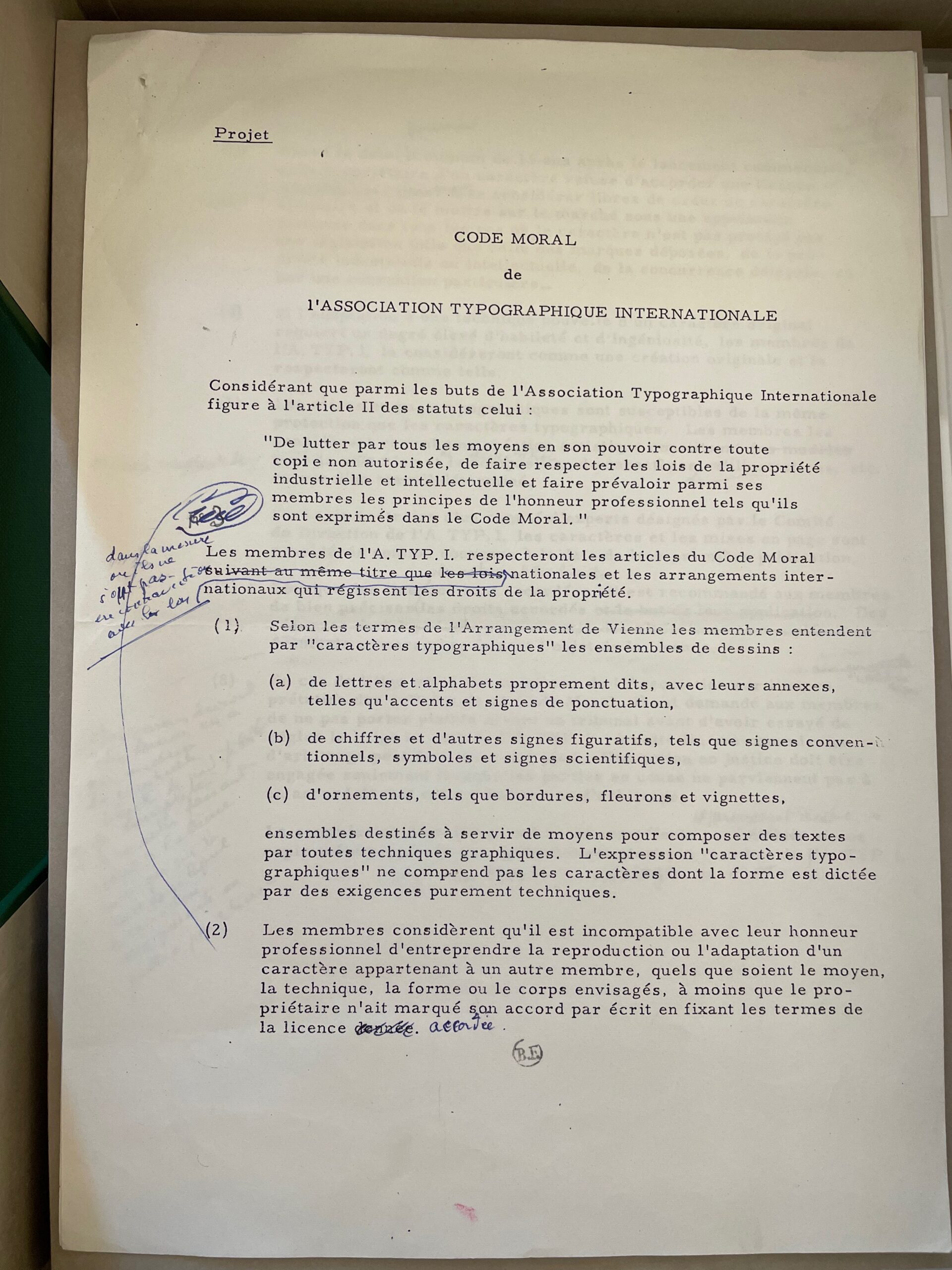

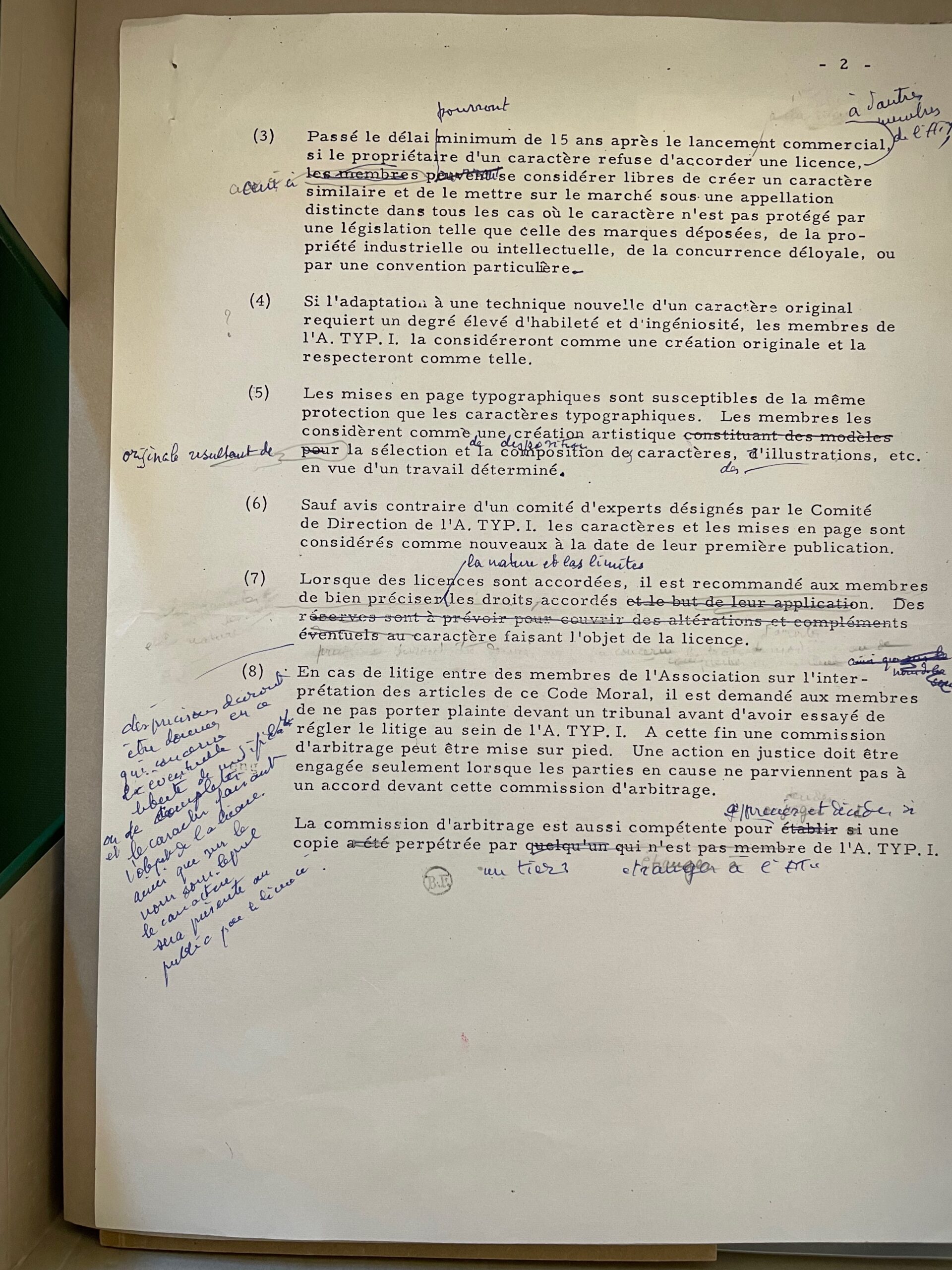

Developing the code

At the July 1957 organizational meeting in Lausanne, the discussion focused on how to define copying in terms of type design, and how to establish limits on rights of reproduction. From the start, they were talking about creating a moral code that the members would commit to following.

Exactly what shape that code should take was a matter for much more discussion, and it lasted over several years. While Me. Poulin negotiated and lobbied with the international standards bodies, ATypI’s committee debated the thorny questions of how type design could be effectively regulated.

By late 1960, vice-president John Dreyfus had prepared a draft of the Code Moral and asked that it be sent to “the Bureau and the Conseil D’Administration” for comment. He also told Peignot that “it would be most valuable to produce a confidential document giving a suggested tariff.” In other words, how much to charge for licensing type designs.

In September 1961 Dreyfus wrote to Peignot that he was still waiting, none too patiently, for Dr. Gerhardinger to give him the “German view-point.”

I have been waiting for Gerhardinger and his son-in-law to let me have their written comments on the draft of the Code Moral. Could you ask Madame Commergue to write to Dr. Gerhardinger: it would be helpful to the members of my Committee to have your comments on the German view-point.

The discussions were still going on when Dreyfus wrote a report from the Type Design Committee on 9 May 1963:

In conformity with the 4th resolution adopted at the Annual General meeting in Verona on 22nd May 1962, the Cormittee re-examined provisions of the Draft Moral Code. Discussions were held in Amsterdam on 4/5 July 1962 between Messrs Born, Dreyfus, Ovink and Tracy, who reached agreement on the text of a revised draft. This draft was subsequently submitted to a meeting of the Board of Directors held at Paris on 25 September 1962, and with minor amendments it has now been approved by the Board. The text has been circulated to all members of the Association, and it is hoped that it will now receive universal acceptance, and that the authority of the Association will be strengthened by the acceptance a Moral Code, the need for which was acknowledged in Article II of the Statutes.

A central deposit for type designs

Concurrent with efforts to formulate a code, there was an early proposal to establish an official “deposit” for typeface designs, a central record office where they could be registered and thus recognized as original designs. There were various ideas about how this should be done, but most of these ideas came to no conclusion. One unresolved question was whether the registry should be limited to new designs or if existing designs could be protected in this way, and, if so, for how long. Even in Germany, where industrial design protection was strongest, there wasn’t necessarily any means of enforcement.

Matthew Carter recalls:

In the absence of any legal protection, there was an idea that I think started with the designers that there should be a sort of voluntary deposit, where we designed and printed a form, which required certain information about a typeface – you could guess what it was – and we established at St Bride’s Library in London a physical deposit where these forms went. Like many of these schemes, it went on very enthusiastically for a year or two and then started to peter out. John Miles and I had the job, before every annual ATypI meeting, of going to St Bride’s to sort of ‘vet’ the deposits. Because in Germany, you know, they had a deposit system for legal protection, and they found that several people had deposited Palatino as their design. So it was potentially open to abuses.

So that, like many other ATypI initiatives, petered out, really.

Implementation

Once the Code Moral had been adopted, a means had to be found to make it effective. Peignot’s grand ideas about protection through the Council of Europe ran aground on the rocks of bureaucratic and institutional procedures.

At first it seemed that the effort should go through an organization called “Bureaux internationaux réunis pour la protection de la propriété intellectuelle” (united international offices for the protection of intellectual property), or BIRPI. But BIRPI, in the person of its director, G.H.C. Bodenhausen, balked at the workload and potential cost required to manage typeface registration and regulation. (Bodenhausen to Peignot, 27 January 1964)

Bodenhausen seems to have been a major impediment to any progress: five years later, John Dreyfus (by then President of ATypI) was privately expressing his frustration with both Bodenhausen and Charles Peignot in a letter to G.W. Ovink:

My discussion at Lurs with Charles was very painful. He accuses me of having brought to nought ten years of work by him. He is obsessed with the idea that we would already have had protection through the Council of Europe if I had acted differently. This is of course patently absurd: the Council of Europe had given an undertaking to Bodenhausen not to proceed with the question until BIRPI had clearly signified whether or not they were going to abandon the question. At least the latest meeting in Geneva makes it clear that the matter will be debated at the Vienna Congress.

Despite Dreyfus’s misgivings about Bodenhausen, the matter was indeed debated at the Vienna Diplomatic Conference (17 May–12 June 1973). Not only was it debated, but it led to the adoption at last of an official agreement: the “Vienna Agreement for the Protection of Type Faces and Their International Deposit.”

The Agreement was signed by ten member states: France, Federal Republic of Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, San Marino, Swizterland, and Yugoslavia. This did not, however, mean that it went immediately into force; that would require that it be officially ratified by at least five countries, “a procedure which may well extend over several years. The Vienna Agreement will come into effect after its ratification in five countries.” (Report of the ATypI Legal Committee, 31 July 1973)

This was when Dreyfus and Peignot posed for their famous photograph outside the Vienna Conference, shaking hands at what seemed to be the culmination of their efforts.

Complications arose almost immediately. As the Legal Committee report noted: “The original intention was the have the Vienna Agreement concluded under the Paris Convention. However, a separate Union has now been constituted especially for the agreement under the control of WIPO [World Intellectual Property Organization].”

The Legal Committee’s report concluded on an aspirational note: “We will continue to devote ourselves particularly to the observance of the Code Moral and will also follow the suggestion made by Dr. Wrolstad during last year’s Congress in Barcelona to try to create an ‘ATYPI’ identification symbol to be used world-wide on all type fonts manufactured by our members.”

Needless to say, no such identification symbol was ever adopted.

1965: Melior vs. Lanston 125

The first documented instance of a serious dispute brought to the attention of ATypI was in 1965, when a Dr. Hörter, the Artistic Director of the Stempel type foundry, wrote to Hermann Zapf to apprise him of a “blatant copy” of his typeface Melior that was being marketed by the Lanston Monotype Company in the United States. The original Melior had been designed by Zapf and issued by Stempel for hand-setting and by Linotype for use on its typesetting machines. Lanston Monotype’s typeface, Lanston 125, intended for use on Monotype machines, was clearly based on Melior.

Hörter approached both Charles Peignot and John Dreyfus to demand that ATypI do something about this plagiarism. In a letter to Dreyfus on 20 May 1965, Hörter challenged ATypI directly:

In our opinion such a case of plagiarism among members of the A.TYP.I offends against the basic principles of that association and it is absolutely necessary for this our association to take steps that the LANSTON 125 be withdrawn. If imitations of this sort were allowed to happen even among members of the A.TYP.I, we think the existence of such an association is no longer justified. We would be grateful to you if you could attend to this matter at the general convention in Zurich and bring about a satisfactory solution.

Dreyfus assured him that after documenting the problem and comparing the two type designs, he would bring the matter to the attention of ATypI’s Commission des Caractères at the 1965 congress in Zurich.

R.K. Ansell, the Executive Vice President of Amsterdam Continental Types, which was based in New York, responded to Stempel’s initial letters (19 April 1965):

I definitely feel that the introduction of Lanston’s new typeface which resemble[s] the Melior will not prove a serious threat to the sales of Melior. If anything at all, it could have a favorable effect on the popularity of the series. It is of interest to note that the installations of Monotype equipment in the United States is negligible. Here in New York City[,] the main center of the industry, there are only 8 Monotype plants. Even these 8 plants have since 1950 found it adviseable to install either Intertype or Linotype equipment. This is mainly because of the availability of the popular type faces on these machines. As you can understand, the hand type and the machine type go hand in hand.

The major concern in this case is the lack of legal protection of ownership rights, which regrettably makes it almost impossible to get satisfactory results against an act of this kind.

Ansell had neatly summed up the practicalities of the situation.

Just to complicate matters, Hermann Zapf documented yet another unauthorized version of Melior being sold in the United States, this time in the form of phototype fonts from the Headliners company. In their catalog, Headliners proudly displayed a phototype knock-off with the transparent name “Melure”: “Now you can keep the clean, precise look of Melior in tight display headings. […] Ask for Melure. Melior is now old-fashioned.”

In the end, it seems that no effective action was taken by ATypI. Certainly Lanston 125 continued to be sold after 1965.

Licensing of type designs

The key question in type-design protection was licensing.

When ATypI was created in the 1950s, the chief sources of type were the manufacturers of mechanical typesetting equipment: Linotype, Monotype, Intertype, Berthold, and a few others. Their fonts were all made to work only on their own machines. Essentially a company’s library of typefaces, and the demand for them in the market, was what sold the industrial equipment that they made their money on.

If a company that originated a typeface was willing to license the design to a competitor, allowing the competitor to make fonts that could be used on their own equipment, then there was no problem. It was just a matter of working out the terms of the licensing agreement, and the price.

But Linotype, one of the heavy hitters in the type business, was unwilling to license its typefaces to other companies (despite the fact that the Code Moral explicitly said that licenses should be available after a certain period of time). Since Linotype’s library included some of the most popular typefaces in the world, this left their competitors with a conundrum. They could create their own typefaces with a similar style, something that was done repeatedly in the 1920s, or their could directly copy the design of a popular Linotype face but market it under a different name. Since there was no legal protection for the design, this practice was all too common.

The problem didn’t change when phototypesetting technology came along: the phototype companies, too, needed fonts that would work only on their equipment, though now those fonts took the form of photographic film rather than metal.

One of the main phototypesetting companies was Compugraphic, which was founded in Massachusetts in 1960. Cynthia Batty, who as Cynthia Hollandsworth was Director of Typeface Development for Compugraphic in the late 1980s and early 1990s and who, as a member of the ATypI board, had worked hard for “font protection that was enforceable and meaningful,” considers the Code Moral to have been “a predatory act against Compugraphic and other phototypesetting manufacturers, who were gaining market share at that time.” The founders of Compugraphic had approached the leading type manufacturers about licensing their designs, and had been turned down.

“U.S. case law,” says Batty, “was very clear that a work of industrial design didn’t have any protection at all. Other countries have it, but if it’s not global, it’s kind of a problem.” So in the face of rejection, Compugraphic went ahead and made its own phototype versions of the popular hot-metal typefaces.

Compugraphic wasn’t the only company that ran up against Linotype’s intransigence. Alfred Hoffmann, the long-time Honorary Treasurer of ATypI, who had managed licensing for the Haas foundry in the 1950s and 1960s, recalled in a 2019 interview that Linotype had insisted on obtaining the Helvetica typeface, which had been developed by Haas. “For us it was an order, since they were majority stakeholders [in Haas]. So in other words it means: ‘We have to have Helvetica […] and we’ll pay you two percent.’ Over time they even paid three percent. However, you mustn’t sell it nor license it to, for instance, Compugraphic, nor to Bobst or anyone else. That means in other words: we have one legal license holder and nine or ten or fifteen excluded ones.”

Licensing and device independence

Everything changed again with the advent of digital typesetting, and particularly with the introduction of PostScript and desktop publishing. Suddenly a typeface was no longer physically limited to a particular kind of typesetting equipment.

Cynthia Batty: “By the time we said that the Code Moral was no longer applicable, it really wasn’t: typeface independence was a fact of life. PostScript changed everything. The Code Moral didn’t anticipate something like device independence. It just wasn’t something that people could conceive of.”

Henceforth the nature of font licensing changed completely. The DTP revolution in the 1980s meant that the designers of new typefaces didn’t have to be employed by giant corporations (though many still were) but could set up in their own homes and bang out a type design on their Macintosh or PC and then sell it as a digital font. It also meant that the users of type could easily make a copy of any digital font without paying for it. The focus of the struggle for type-design protection shifted to individual users and to the new companies that sprang up selling pirated copies of existing typefaces, or even posting them online as free downloads. The age of the EULA (End-User License Agreement) had arrived.

A new Code Moral

In 1995 ATypI updated its statutes, and as a result the Code Moral also needed updating. For the 1996 ATypI conference in The Hague, Cynthia Batty prepared a document for the Legal Committee, outlining the current situation and some of the proposed solutions. Mark Batty introduced this compilation in a “Note from the President”:

The document that we have most often called the Code Moral is outdated and needs changing. In the past it has gone hand-in-hand with the Statutes but was somehow disconnected during the revisions that took place between 1994 and 1996. This provides us with an ideal opportunity to decide what we want and adopt it because the statutes need cleaning up again anyway.

Updating the Code?

The Code Moral was updated at least three times. After the 1973 adoption of the Vienna Agreement, the Code was amended to include a reference to the definition of a font that was used in the Agreement. In 1996, after the revision of the association’s statutes, the Code was again updated, in an attempt to adapt to the changes in both typesetting technology and the type business.

In 2003, after still more technological changes had hit the type business, and after it had become abundantly clear that ATypI had no power to enforce any licensing agreement or to police the market for what are ironically known in French as “polices” (fonts), the Board and the members had to decide whether the Code Moral still served any purpose.

The Board asked Robin Kinross, a respected publisher, editor, and writer who had no connection to any of the companies in the type business, to take a crack at writing a new Code Moral. To aid him in this thankless task, I (as a Board member) put together a document summarizing and quoting the most relevant comments from recent discussion.

There seemed to be three options for ATypI with regard to the Code Moral: 1) keep it in its present form; 2) get rid of it entirely; or 3) create a new code or statement that was relevant to current real-world conditions. The Board decided to take the third option, which is why they approached Kinross to help craft a new statement.

In the end, however, it was the second option that prevailed. After reviewing the existing Statutes and the ongoing arguments, Kinross concluded: “It seems to be generally agreed by the Board, and by the members who have spoken in the email discussions this summer, that the Code as it stands is now obsolete.” He offered a more general “statement of principles,” if the association wanted it, but his primary recommendation was that the Code simply be retired.

At the AGM in Prague in 2004, the members voted to approve a new addition to the Statutes, putting an end to the Code Moral:

(2) ATypI agrees that “the Moral Code of the Association Typographique Internationale” (“Code Morale”) is no longer conforming to the Association’s objectives and therefore decides to retire the Code Morale document without replacement.