My usual self-description is “editor and typographer,” and most of the time this blog concerns itself with the second part of that description. In this blog post, however, I am putting on my editorial hat.

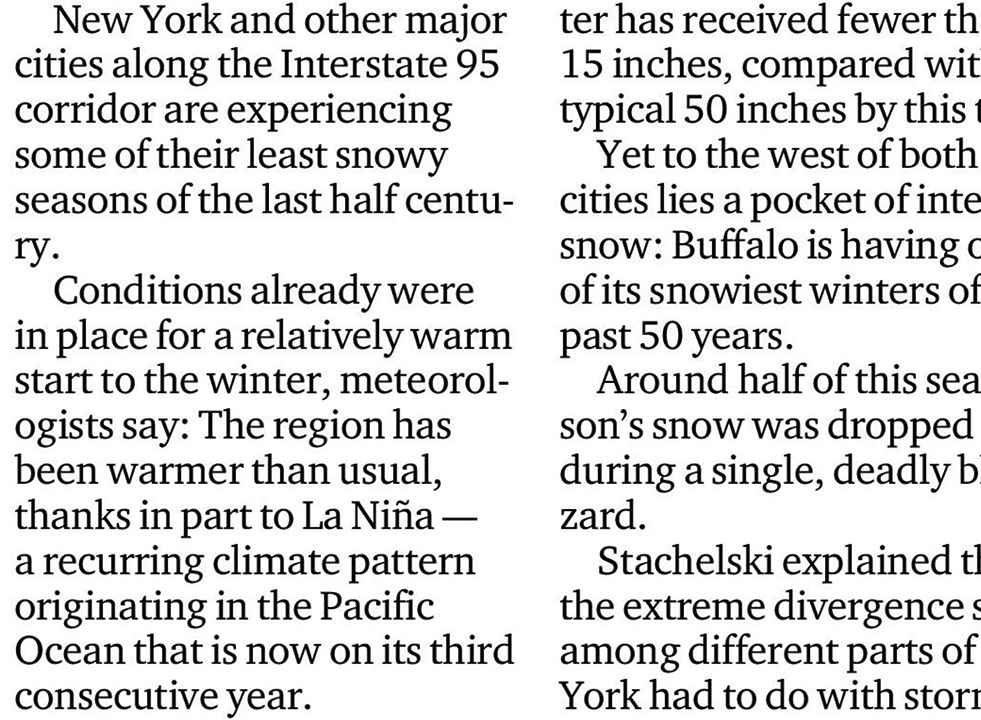

Earlier this month, our local daily newspaper, the Seattle Times, reprinted an article from the New York Times about the lack of measurable snowfall this winter in New York City. As I read the article (in the online “replica” of the printed pages), I was stopped by an awkward bit of wording: “Conditions already were in place for a relatively warm start to the winter, meteorologists say.” Already were?

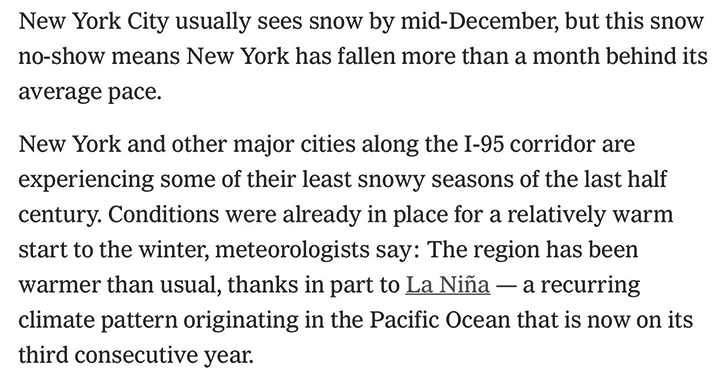

I got curious – curious enough to go find the original article on the New York Times website and scroll down to that paragraph. In the original article, that sentence read, “Conditions were already in place for a relatively warm start…”

Editors often re-edit a news story in various ways, such as chopping this original long paragraph into two short ones. But in this case, an editor at our local Times had changed the completely natural word order (“were already in place”) into something awkward and unnatural (“already were in place”). Why?

I think it comes from some mistaken ideas about where adverbs normally fall in English sentences. Words like “still” / “already” / “often” / “probably” find their most natural place after any form of the verb “to be.” When the verb has two parts (a compound verb), the place for such an adverb is between the two parts: the adverb is usually found in the middle. That is both the natural rhythm of a spoken English sentence, and the placement that most grammarians and stylists agree is correct.

But somewhere along the line, someone came up with the notion that you shouldn’t “split” a compound verb. I’ve just learned, after a bit of googling, that this is known as the “split verb rule.” I also found a lovely and lengthy analysis on Language Log of where this bogus rule came from and exactly why it makes no sense. Quite simply: the natural place for an adverb is between the parts of a compound verb.

This supposed rule, like its cousin the “split infinitive rule,” must have been invented by hair-splitters. The usual excuse is to hark back to Latin, where an infinitive is a single word (findere) and there’s no way to split it. But an English infinitive is two words (to split), which naturally invites any relevant adverb to fall in the middle. Trying to extend this unnatural idea to compound verbs is even sillier than avoiding split infinitives. Both “rules” ought to be laughed off by any good writer. Or editor.

The example I gave from the two Timeses doesn’t involve a compound verb, but I suspect that the second editor was influenced by the split verb rule (which the paper definitely seems to believe in) and treated “were in place” as a phrase that shouldn’t be broken. But it should be.

Seattle Times, are you listening?

[Images: paragraphs from the same news story in the New York Times (top) and the Seattle Times (bottom).]